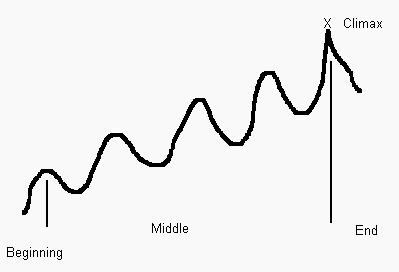

As noted in the Assignment 3 Lecture on character, only three elements are necessary to create fiction: character, conflict, and setting. Character and conflict are the two elements most pertinent to the successful analysis of a story. So, a thorough understanding of the mechanics of character and conflict is a key to analysis. The static or dynamic nature of a character is produced by the outcome of the conflict, so the two elements are intertwined. I suggest you look back on occasion at the crude schematic of the mechanics of a story at the end of the Basics of Fiction Analysis document. The information in the box is the essence of the story.

Contents

Contents

What Is Conflict?

Types of Conflicts

Plot

Basic Plot Line

Story Structure

Other Elements of Plot

Analyzing Conflict

Detailed Example of Conflict Analysis

Writing the Assignment 4 Conflict Analysis

Sample Conflict Analysis - Assignment 4

ASSIGNMENT 4 REQUIREMENTS

Guidelines for Submitting Your Assignment Files

Most short stories consist of the introduction, development, and resolution of a conflict. A conflict is a problematic situation with which the character must contend. This situation usually results in the clash of opposing forces and a consequent struggle. This struggle may be a clash of traits, actions, wills, ideas, desires, ambitions, or morals.

Problems can take the form of humans, animals, fate, forces, emotions, traits, behaviors, and attitudes, or various elements of the world/cosmos, such as God or aliens. Conflicts can be physical, psychological, moral, or emotional in nature.

The central character, or protagonist, usually has several problems in a story. The most critical problem is called the central conflict, the one because of which the other problems arise. In most substantial short stories, the central conflict will be an internal one. The less critical problems are called minor conflicts, or complications. These minor problems are often regarded as the action of the story.

The protagonist's desired outcome of the primary minor (or external) conflict is called his goal. The reason he desires that outcome is his motivation; the motivation is also usually the character's beginning key trait. For example, in "The Necklace," Mathilde's desired goal is to win admiration at the ball. She desires this goal because of her self-deceit, her belief that she is of a higher class than she really is. This self-deceit is Mathilde's beginning key trait.

A note about goals: A character's external goal is often quite apparent--to win a race, to catch the bad guy, to get the girl. A character's internal goal is often not so apparent; in fact, many characters do not even know they have an internal conflict, so they do not have a clearly expressed internal goal. Usually, though, the motivation is the basis of the internal conflict. Why the character seeks the goal is his motivation, which is linked to the beginning key trait. As an example, Shakespeare's Macbeth wants to become king because he is ambitious. His motivation is his ambition. His beginning key trait is also that overwhelming ambition that causes his character to be out of balance.

Those things that hinder the protagonist's progress to his goal--the opposing forces--are called antagonists, complications, or obstacles. These can be persons, things, social conventions, character traits, the protagonist's own personality or morality, etc.

A formula for finding conflicts: P + G + O = C or

protagonist + goal + obstacles = conflict |

There are two forms and three types of conflicts. One form of conflict is the external conflict. An external conflict takes place outside a character. It can be mental or physical in nature. The two general types of external conflict are man vs. man (or collectively, man vs. society) and man vs. cosmos. This second type can include nature, the elements, the environment, fate, God, etc.

The second form of conflict is the internal conflict. An internal conflict takes place within a character. It is the man vs. himself type. The internal conflict can be psychological, moral, or emotional in nature. Always try to find this type of conflict as the central conflict in a story. Half of this conflict will be the beginning key trait. The other half will be an opposing trait (i.e., the ending trait in a dynamic character).

The outcome of the conflict is called the resolution or denouement. At the climax of the story, the outcome of the conflict becomes evident. The problem may be resolved satisfactorily or unsatisfactorily for the protagonist. A new state of affairs is introduced; this state of affairs is produced by the outcome of all the conflicts. Perhaps the Big Loser wins the lotto and becomes optimistic about life again, too. This new state of affairs will include either a dynamic change for the protagonist or no change at all.

"An appealing or sympathetic character struggles against great or overwhelming obstacles to attain a worthwhile goal."

With this formula, which mostly applies to external conflicts, three types of ending are possible.

A typical plot goes through a series of steps as it develops:

Potential situation: a situation or a setting out of which conflict has the potential to develop. This introductory scene is part of the beginning of the story. In this section the author often provides exposition, or the exposing of important information that allows the reader to understand events that follow. Information about the central character is often included, so that the reader can start to determine the central character's beginning key trait.

Inciting incident: the occurrence or triggering action that begins the chain reaction leading into conflict. This incident marks the end of the beginning and the start of the middle of the story. At this point, the plot moves from potential to kinetic, with the motive force the motivation, or beginning key trait, of the character.

Conflict: the obstacles that face the protagonist, one major and several minor. Conflict also includes the clash of opposing forces and the resultant struggle. The major conflict is dealt with in the middle of the story.

Complications: the minor obstacles (minor conflicts) that hinder the protagonist's progress toward the external goal, or the resolution of the primary external conflict. The complications are also dealt with in the middle of the story.

Climax: the turning point of the story. The climax marks the point of highest emotional intensity in the story. At this point, the reader becomes aware if the central character will attain the goal. The reader also knows which side of the internal conflict, or which key trait, prevails at the end. The climax marks the end of the middle.

Resolution: also called the denouement. This section yields the solution of the character's problem--the resolution of all the conflicts. One trait or the other prevails. The protagonist either attains his goal or fails. A new state of affairs resulting from the outcome of the conflict is introduced. The reader can determine if the central character's beginning key trait has changed (dynamic character) or remained intact (static character). An emotional tone may also become apparent to the reader as a result of the outcome. This section of the story is the ending, and it contains valuable information for a successful analysis.

Another element of the plot line is the moment of ultimate despair. The moment of ultimate despair is that point (in a story with a happy ending) just before the climax at which the protagonist looks ready to lose the conflict. It is the black moment--when Mighty Mouse is hanging by his cape from the moon, when Marshal Dillon wavers momentarily following a gunfight, when the groom looks as if he won't make his wedding on time. But then a reversal occurs, the protagonist summons new energy, and he goes on to win the conflict. The moment of ultimate despair is meant to build sympathy for the positive protagonist.

A typical short story will have three to five scenes. Each scene should have a minor conflict, just as the story has an overall central conflict. As these minor conflicts are developed and resolved, the story will seem to move forward toward the resolution of the central conflict.

The beginning: the introductory scene or potential situation. The opening of the story should provide a hook for readers to give them incentive to read on (mysterious situation; intriguing character or conversation; appealing setting or mood; engaging writing style). The introductory scene should also include:

Plot Diagram

Plot Diagram

Though character and conflict are separate elements, they are closely tied in the successful analysis of a story. As the Basics of Fiction Analysis document and schematic suggest, the internal conflict is really just the struggle between the opposing traits that are grappling for control of the character's behavior. Identifying the beginning key trait allows you to deduce the opposing trait, and the two traits then can be plugged into the internal conflict. At any point prior to the climax, a character with an apparent change can revert to former ways. The climax seals the fate of the character, and no reversal is possible after the climax. As a result, you should only use evidence from the climax or following to support your analytical claim of static or dynamic character.

For a successful analysis of character, identify the key trait of the central character at the beginning of the story. Then, show how the beginning key trait motivates the character's actions through the middle of the story. Identify the central character's key trait at the end of the story. Finally, provide evidence from the climax or following to show that the character's key trait has changed or has not changed. Keep in mind that for a character to be considered dynamic, a permanent internal change must have occurred. A temporary change before the climax does not constitute a dynamic change. An external change in appearance or circumstances also does not constitute a dynamic change. Death also does not make the central character dynamic. Again, the dynamic change must be internal, permanent, fundamental, and profound.

The struggle of the traits is fought on an internal landscape, so always look for an internal conflict as the central conflict. Without an internal conflict, the key trait of the central character becomes insignificant. Without a key trait, the central idea becomes insignificant. Again, if you can identify the beginning key trait, you have located half the internal conflict. The other half will be apparent at the end of the story, or you can deduce it as the opposite of the beginning key trait. The climax of the story and evidence following the climax demonstrate that one or the other of the traits prevails at the end, making the character static or dynamic.

During the middle of the story, the internal conflict spawns a series of minor conflicts that lead the character into deeper and deeper trouble. Young Dave in "The Man Who Was Almost a Man" has the internal conflict of immaturity vs. maturity, with immaturity as his beginning key trait. His immaturity causes him to lie, break promises, and act irresponsibly in a series of mishaps. Each mishap makes his situation worse. Point out the most important mishaps, or minor conflicts, in your discussion of conflict. Also identify the specific event that serves as the climax of the story. Do not simply suggest that the climax occurs near the end of the story, because that statement is true for most all stories. Show the effect of the outcome of the conflict on the character, which is basically to make the character static or dynamic.

A thesis statement for an analysis of conflict (as in Assignment 4) should suggest that the central conflict is an internal conflict and should identify the character as static or dynamic. See the thesis statement in the sample analytical essay below.

The author establishes Mathilde's character and her imbalance early in the story. She is a middle-class woman who thinks she is poor but who believes she was destined to be rich. As Maupassant points out in the second paragraph, "she was as unhappy as though she had really fallen from her proper station." This is a key line in establishing Mathilde's key trait. The author does not suggest that fate had cheated Mathilde or that she really should have been in the upper class. He says, "as though she had really fallen."

Another key line is in the beginning of the third paragraph: "She suffered ceaselessly, feeling herself born for all the delicacies and all the luxuries." So, Mathilde has deceived herself into thinking she rightfully belongs in the upper class with all its trappings, and she ignores all the qualities she has going for her: "beauty, grace, and charm." In addition, she has made herself miserable by failing to realize what she does have: a middle-class life, a maid, a dutiful husband, the occasional night at the theater. But all these benefits fade when she dreams about what she thinks she deserves.

Her beginning key trait, then, can be stated in a variety of terms: self-deceit, conceit, arrogance, materialism. For our purposes, let's choose self-deceit and see how all Mathilde's actions are motivated by her errant belief that she was born in the wrong class. In addition, Mathilde displays many unpleasant characteristics. She is discontented and full of self-pity, caused by her self-deceit. She feels cheated in life and a victim, suggested by her residence on Rue des Martyrs, the street of martyrs. She thinks material possessions equal status, showing her materialism. She thinks she is better than other women of her class, showing her arrogance. She is envious, covetous, and vain, showing her lack of real values. Remember, you should ask yourself why a character feels or acts the way she does. If you ask yourself why Mathilde feels all these things, the answer is her self-deceit, her belief that she was born in the wrong class.

So, if we take Mathilde's beginning key trait of self-deceit and balance it with the opposing trait of reality, we have Mathilde's central internal conflict, which is self-deceit vs. reality or fantasy vs. reality.

As the story progresses, Mathilde is motivated by her self-deceit. She is disappointed when she sees her peasant maid because she dreams of living in a palace. When her husband marvels over stew, she dreams of quail wings served on dainty dishes. She is not satisfied with what she has. She only lusts for more. The classic poet Seneca wrote, "It is not he who has little but he who always wants more who is poor." Mathilde is poor only because she has deceived herself to believe she deserves more than is alloted to her in her middle-class life. In reality, she leads a comfortable middle-class life, but Mathilde fails to realize or appreciate her real situation.

When her husband receives an invitation to the prestigious ministry ball, she at first does not want to go. She complains that she has nothing to wear. Her husband suggests she wear her theater dress, but that is not good enough for Cinderella Mathilde. She tells her husband to give the invitation to some husband "'whose wife is better equipped than I.'" One can see that Mathilde believes material possessions--equipment--make her better than others. Her husband is a modest man who serves as a foil to represent her reality. He appeases her material lust and solves this complication by offering his savings to buy her a dress. Her self-deceit that she is in the upper class has caused the need for the dress; she has to look the part.

Still she is not satisfied because she has no jewels. Her husband suggests she wear flowers. Her response is that "'there's nothing more humiliating than to look poor among other women who are rich.'" Of course, she is not really poor, and many of the other women at the ball will be middle class, just like her. To solve this complication, her husband suggests that she borrow some jewels from her rich friend, Mme. Forestier. This friend serves as a foil who represents Mathilde's false self-image as upper class.

When Mathilde visits Mme. Forestier, her friend lets Mathilde choose anything she wants. Instead of being suspicious why her friend would lend her such expensive jewelry, Mathilde is overcome by "immoderate desire" and keeps asking for more. Finally she finds a "superb necklace of diamonds" to satisfy her fantasy. She puts on the necklace and is "lost in ectasy at the sight of herself." Mathilde's self-deceit has again caused her to appear rich to fit the part she has imagined for herself.

The day of the ball arrives. Mathilde is a hit at the ball. Instead of crediting her beauty, grace, and charm, she believes that she is noticed because of the necklace. After the ball, she joins her husband, who has been napping because he must work the next day. The following part of the story clearly shows Mathilde's central conflict of self-deceit vs. reality.

Her husband "threw over her shoulders the wraps which he had brought, modest wraps of common life, whose poverty contrasted with the elegance of the ball dress. She felt this, and wanted to escape so as not to be remarked by the other women, who were enveloping themselves in costly furs."

The clash of the ball dress with the wraps represents her conflict.

She rushes out of the ball, somewhat like Cinderella, so as to preserve her false illusion. In her haste, she loses the necklace. This loss is an important part of the story, but it is not the most important part. Many students think she accidentally loses the necklace, or the loss is an act of fate. Clearly, her rush to preserve her fantasy is the cause of the loss of the necklace.

When the Loisels return home, Mathilde notices the necklace is lost. Her husband goes out looking for it but cannot find it. At her husband's dictation, Mathilde sends a note to her friend. In the note, she lies and says the necklace is being repaired. Her prideful desire to preserve her false self-image causes her to lie. Imagine how easy it would have been to say the necklace had been lost. Considering the end of the story, wouldn't Mathilde's life have been so much easier if she had only faced reality? Keep in mind, though, the loss of the necklace and the lie about the loss are only complications (minor conflicts) in the story. The loss and the lie are both caused by Mathilde's beginning key trait of self-deceit.

But Mathilde does not face reality at this time. Instead, they replace the necklace and go into deep debt. When Mathilde returns the necklace, Mme. Forestier is rather chilly. Mathilde is glad her friend does not examine the necklace because Mathilde does not want to be regarded as a thief. Being a liar, though, is apparently fine with her.

Mathilde suddenly takes on the repayment of the debt heroically. The maid is let go, and Mathilde and her husband must move to a smaller apartment. During the ten years of repaying the debt, Mathilde becomes a common woman who must work hard, mop the floors, haggle over every franc, and do all the things she once so disdained. In the process, she loses her beauty, charm, and grace. At the end of the ten years, when the debt is paid off, the author describes Mathilde as she sits by the window:

"Mme. Loisel looked old now. She had become the woman of impoverished households--strong and hard and rough. With frowsy hair, skirts askew and red hands, she talked loud while washing the floor with great swishes of water. But sometimes, when her husband was at the office, she sat down near the window and she thought of that gay evening of long ago, of that ball where she had been so beautiful and so [admired].What would have happened if she had not lost that necklace? Who knows? Who knows? How life is strange and changeful! How little a thing is needed for us to be lost or to be saved!"

In the window scene, does Mathilde realize why she had to suffer for the past ten years? Does she blame her self-deceit for all her problems? No, apparently not. What would have happened if she had not lost the necklace? She would still be beautiful and charming and full of self-pity and self-deceit. What was the little thing that doomed her? The lie she told to preserve her fantasy, of course. Does she admit her fault? Not at all, so at this point in the story she has not changed internally. Externally, she no longer has the positive qualities she ignored at the beginning of the story. Now she does not have money, beauty, charm, or any of the things she sought earlier, but she still has her fantasy. But the climax has not been reached, so the determination of static or dynamic cannot be made yet.

The last section of the story contains the climax of the story. Depending on your interpretation, the climax can appear at one of two places--either when Mathilde decides to approach Mme. Forestier or when she confesses replacing the diamonds and smiles with joy. I will explain more thoroughly later, but first, let's look at particulars.

One Sunday, Mathilde is out walking on the Champs Elysées in the rich part of Paris. Why is she, a common and rough woman, there? The story says she has come to "refresh herself." Perhaps she is window-shopping at Palais Royal, still lusting after material goods. Anyway, she by chance encounters her old friend, Mme. Forestier, and based on Mathilde's perception, her friend is "still young, still beautiful, still charming"--all the things Mathilde still could have been had she not lied about the loss of the necklace, or had she not had her self-deceit to begin with. Do you note a sense of envy in Mathilde?

Mathilde debates whether to approach Mme. Forestier. Since she had paid up, she would tell her friend all about the last ten years. Mathilde approaches Mme. Forestier, and her friend does not recognize her.

Mme. Forestier says, "'Oh, my poor Mathilde! How you have changed!'" Mme. Forestier is remarking on Mathilde's changed external appearance, which cannot be used to support a static or dynamic determination.

In the next line of dialogue, Mathilde, still true to form, blames someone else for her problems: "'I have had days hard enough . . . and that because of you!'" Does Mathilde accept responsibility for her own downfall? No, of course not.

Then Mathilde admits that she lost the necklace. Recall that earlier she lied and told her friend the necklace was being repaired. She never told Mme. Forestier the necklace had been replaced. So, this admission resolves the lie about the loss of the necklace. However, as suggested earlier, the lie about the loss of the necklace is a minor conflict. The outcome of her central conflict of self-deceit vs. reality has not yet been determined.

Mathilde then admits that she and her husband replaced the necklace and she says it was very hard to do because they "'had nothing.'" Does she realize how well off she was at the beginning? No, of course not.

Mathilde says that the replacement necklace was "'very like'" the original necklace that was lost. Then "she smiled with a joy which was naive and proud at once." And then Mme. Forestier drops the bombshell that the original necklace was made of paste. It was simply costume jewelry, but this last revelation is really not important to the story other than to give poor Mathilde one more jab in the ribs.

But let's look at what has transpired in this last section. You would use this last section of the story to justify your choice of Mathilde as static or dynamic.

If you believe that Mathilde is dynamic, your best approach is to say that the climax is when Mathilde decides to approach Mme. Forestier. Remember, at the beginning, Mathilde was consumed by appearances. She thought that appearances made a person who she was. Well, at the end, Mathilde is old-looking and haggard, but she decides to approach her old friend anyway, not really concerned by her appearance. Mathilde also tends to use "we" more than "I" toward the end of the story. Those few scraps are pretty much the dynamic evidence.

Of course, you could say that Mathilde only approaches Mme. Forestier to blame her for her own problems, which she does. If you recall, at the beginning Mathilde was envious, covetous, vain, proud, selfish, arrogant, self-pitying, irresponsible, conceited, and deluded. Is she still those same things at the end? Let's consider.

When Mathilde first sees Mme. Forestier, she perceives her beauty, youth, and charm with a sense of envy. She blames Mme. Forestier for her problems, so she is still irresponsible. She says they had nothing, so she still is full of self-pity and delusion. She admits at the end that the fake necklace and the real necklace were very much alike, so she is still unable to distinguish the real from the false, which is the root of her self-deceit. And when she smiles with joy, it is a joy that is arrogantly proud for having paid off a debt which she believes was not her fault, and it is naive or innocent because, again, she was not at fault. All this evidence suggests a lack of change. Self-deceit seems to be her ending key trait.

If you believe that Mathilde is static, then the climax would be when she smiles with joy near the end for having sacrificed her life to repay a debt she still believed was not her fault.

I don't know how you feel about Mathilde at the end. I don't have much sympathy for her. But the truly sad thing about Mathilde is that she sacrificed something of true value (her beauty, charm, grace, wit) in pursuit of something that was false (her perceived status).

Here are some interesting tidbits about the story you might have overlooked. The fake necklace is, of course, a symbol of Mathilde's false image of herself. The false image is lost and replaced by the real, but only in the sense that she must become a woman of the common people. She admits at the end that she is still unable to distinguish between the real and the fake.

Additional evidence to bolster a static character claim comes from the setting and from Mathilde's reaction to her situation. At the beginning, she thinks she has been cheated in life. In a sense, she feels she has sacrificed her life for the benefit of others, so she lives appropriately on Rue des Martyrs, the street of martyrs. In the middle of the story, when she must repay the debt that is, after all, her own fault, she takes on the task heroically. What is so heroic about paying off a debt that is your own fault? Nothing, of course, but in her self-deceit Mathilde perceives herself as a hero. Finally, at the end of the story, Mathilde is on a famous street in Paris, the Champs Elysées. The name of this street is an allusion to the Elysian Fields. The Elysian Fields were for the purified souls of the dead who had led an upright life. These souls would spend their afterlife in eternal springtime and sunlight. Using these story details, we see that Mathilde's perception of herself goes from martyr to hero to blessed soul. So where exactly is the change in her character? I don't see one.

The sample essay below suggests an appropriate content for the conflict analysis you will write for Assignment 4. The central idea is in CAPITAL LETTERS, and the thesis statement is underlined.

The sample essay below is single-spaced. Your typed essay must be double-spaced.

Your introductory paragraph for this essay must include:

Your introductory paragraph for this essay must include:

In your essay you must include these components:

An Unhappy Ending for Cinderella

Guy de Maupassant's "The Necklace" is about a vain woman whose life is filled with self-deceit. The central character, Mathilde Loisel, has convinced herself that she belongs in a higher class, with all its material trappings. When her husband gains an invitation to an exclusive ball, she feels compelled to borrow a diamond necklace. She loses the necklace, lies about the loss, and falls into years of poverty to replace the jewelry, only to discover at the end that the borrowed necklace was a fake. Maupassant uses the internal conflict and static character of Mathilde to suggest that DECEIVING ONESELF CAN OFTEN LEAD TO REGRETTABLE CIRCUMSTANCES.

At the beginning of the story, Mathilde is unhappy with her station in life. She believes that fate had blundered and that she deserves better. Instead of accepting her true qualities of beauty, charm, and wit, she instead laments her lack of possessions, suggesting her obsession with appearances. She believes she is better than her friends and even her husband, showing her conceit. She feels that she has been been cheated and that she is a victim, showing her self-pity. Of course, her beliefs are not valid; the author clearly points out that she only believes she deserves better, and she lets her errant beliefs cause her misery. As a result, her beginning key trait of self-deceit becomes pronounced.

Mathilde's central internal conflict of self-deceit vs. reality, or fantasy vs. reality, is apparent from the beginning. Mathilde cannot tell the real from the false in her life. When her husband gains the invitation, she claims she has nothing to wear. Her frugal husband, a foil who represents her reality, suggests that she wear her theater dress and flowers. Mathilde tells her husband to give the invitation to some man "'whose wife is better equipped'" than she is, pointing out her need of material things to substantiate her errant self-image. A new dress easily solves one minor conflict, but she is unsatisfied. She needs jewels to complete the illusion because, as she says, "'there's nothing more humiliating that to look poor among other women who are rich.'" She decides to borrow jewelry from her rich friend, Mme. Forestier, a foil who represents Mathilde's illusion. A borrowed diamond necklace completes her illusion, and a Cinderella is born. She is a hit at the ball, a feat she credits to the necklace. As she leaves in a rush so as not to be detected in a modest cloak "whose poverty contrasted with the elegance of the ball dress," she loses the borrowed necklace. Indeed, this contrast of apparel highlights Mathilde's internal conflict, fantasy vs. reality.

When Mathilde discovers the loss, she could confess and settle the matter. But the necklace she lost represents her own false self-image, which she does not want to lose, so she cannot admit the loss. She deceives again, this time an external lie to Mme. Forestier that leads to the minor conflict of ten years of debt as she and her husband secretly replace the lost necklace with an expensive substitute. The years of hard labor to repay the debt cause Mathilde to lose her youthful beauty. She becomes hard and haggard, but this change is only external. At times, she still harkens back to the ball and blames her downfall on the careless loss of the necklace, not on her unending pattern of self-deceit.

The static nature of her character is clearly demonstrated when she meets Mme. Forestier on the Champs Elysées. Ten years have passed, the debt has been repaid, and Mathilde decides to confess the lie about the loss. Her confession, unfortunately, only resolves a minor conflict, and her continued self-deceit is evident. Mathilde still has a sense of envy as she approaches Mme. Forestier, who is "still young, still beautiful, still charming." Worse, Mathilde blames Mme. Forestier, not herself, for her downfall, showing her continued irresponsibility. She further claims she and her husband had nothing to begin with, though they were middle class, showing her continued delusion. The climax occurs when she admits her continued inability to distinguish the real from the false: the two necklaces "'were very like,'" she says. And then she smiles innocently and arrogantly. One can only wonder about Mathilde's reaction when she learns the borrowed necklace--the shiny symbol of her own false self-image--was only a worthless fake.

Mathilde's beginning key trait of self-deceit remains throughout the story, marking her clearly as a static character. She goes from a martyr to a hero to a saint, a conceited and deceitful woman who never comes to accept her true station in life. Sadly, Mathilde sacrifices her real qualities--beauty, charm, wit--in pursuit of something that is false. Perhaps Mathilde would have profited from the words of the ancient poet Seneca: "It is not he who has little but he who always wants more who is poor."

The sample essay is about 800 words long. Your Assignment 4 essay must be at least 500 words long and at least four paragraphs long.

Notice in the introduction in this sample that the title and author are clearly indicated, as is the identity of the central character. Only key events are presented, and the central idea (in CAPITAL LETTERS) is in the form of a complete statement. The underlined thesis statement clearly and directly identifies the kind of central conflict and the character as static. The body paragraphs give information about the character at the beginning, the central conflict and its development, the climax, and the static nature of the character at the end.

The second paragraph of the sample essay introduces the character at the beginning of the story, shows some of her behaviors, and establishes her beginning key trait.

The third paragraph of the essay identifies the central conflict of the story and shows how the character's beginning key trait is not only part of the central conflict but also the motivation for many of her actions. A minor conflict is also identified. Minor characters who serve as foils to Mathilde are also introduced.

The fourth paragraph of the essay identifies the necklace as a symbol of Mathilde's false self-image. This paragraph also identifies the most important minor conflict in the story, the lie about the loss of the necklace that begins Mathilde's ultimate downfall. The external changes she undergoes are noted, but these changes are not mentioned as evidence of a dynamic change.

The fifth paragraph of the essay identifies the climax of the story and gives evidence to support Mathilde as a static character. Mention is made that the important minor conflict about the loss of the necklace is resolved, but the key trait does not change.

The conclusion restates the central conflict and reiterates the lack of change in Mathilde. The central idea is restated, and the essay ends with a quote that summarizes Mathilde's character and conflict.

First, read a story from the list below. Reading the story at least twice is recommended. These stories are in Fiction 100.

Assignment stories:

Second, write an analytical essay of at least four paragraphs. Use the referential-interpretive purpose to write your analysis.

Develop a thesis that deals with character and conflict in the story. What is the central conflict of the story, and does it produce a static or dynamic central character (protagonist)? To answer this question, you will need to describe the central character at the beginning of the story and then at the end. Focus on one beginning key trait or value, and show how that trait or value motivates the character's actions. Identify the beginning and ending key traits directly in the body of your analysis. Identify the character directly as static or dynamic in the body of your analysis. If the character is dynamic, trace the development of the change that occurs. Specify the point at which the dynamic change occurs and the nature of the change. If the central character is static, show how the character, despite the central conflict and its outcome, could be motivated to continue without change. For your argument, use solid evidence from the end of the story, at or after the climax you identify.

Also include a detailed discussion of conflict in the story. What general type of central conflict is used? Is it internal or external? What specific forces are at odds? Identify the central conflict directly as ___ vs. ___. Show how the conflict is developed and resolved. Identify the climax of the story directly and specifically, not as some general point in the story. Indicate other specific points on the plot line, such as the potential situation and inciting incident. What effect does the outcome have on the protagonist?

As much as possible, combine the discussions of character and conflict. I prefer an integrated discussion instead of two separate discussions.

Length: 500 - 600 words

All students must complete Assignment 4.

Submit this assignment using the Submissions button in Blackboard.

If you are not sure how to submit your assignment file by now, review the guidelines at this link to Assignment 2.