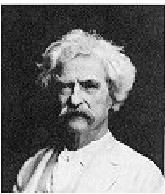

"Two Views of the River," by Mark Twain

ASSIGNMENT SELECTIONS

"My Boyhood on the Prairie," by Hamlin Garland

"Empty Hands," by Jane Addams

"Race Evils," by Rev. G.W. Johnson

"San Antonio, 1841," by Mary A. Maverick

"Hunting the American Buffalo," by Theodore Roosevelt

"Black Hawk's Surrender Speech"

"The Story of an Eyewitness," by Jack London

"Austin, 1861," by Amelia Edith Barr

"Puberty and Adolescence in Girls," by Mary Scharlieb, M.D.

"The Boyhood of Lincoln," by Elbridge S. Brooks

SAMPLE SELECTION

Two Views of the River

by Mark Twain

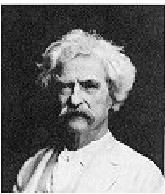

Mark Twain (1835-1910) was the pen name of Samuel L. Clemens. When Twain was four, his family moved to Hannibal, Missouri, on the banks of the great Mississippi River. In his younger days, Twain dreamed of becoming a riverboat pilot. He got his chance around 1860, but the Civil War soon put an end to that career.

Twain recounts his riverboat days in Life on the Mississippi, published in 1883 by Dawson Brothers, Montreal. The excerpt below is from pages 97-100 in Chapter IX.

Use this reading selection in conjunction with the sample analysis in the Assignment 6 Lecture.

|

Two Views of the River

by Mark Twain

The face of the water, in time, became a wonderful book--a book that was a dead language to the uneducated passenger, but which told its mind to me without reserve, delivering its most cherished secrets as clearly as if it uttered them with a voice. And it was not a book to be read once and thrown aside, for it had a new story to tell every day. Throughout the long twelve hundred miles there was never a page that was void of interest, never one that you could leave unread without loss, never one that you would want to skip, thinking you could find higher enjoyment in some other thing. There never was so wonderful a book written by man; never one whose interest was so absorbing, so unflagging, so sparkingly renewed with every re-perusal. . . .

The face of the water, in time, became a wonderful book--a book that was a dead language to the uneducated passenger, but which told its mind to me without reserve, delivering its most cherished secrets as clearly as if it uttered them with a voice. And it was not a book to be read once and thrown aside, for it had a new story to tell every day. Throughout the long twelve hundred miles there was never a page that was void of interest, never one that you could leave unread without loss, never one that you would want to skip, thinking you could find higher enjoyment in some other thing. There never was so wonderful a book written by man; never one whose interest was so absorbing, so unflagging, so sparkingly renewed with every re-perusal. . . .

Now when I had mastered the language of this water and had come to know every trifling feature that bordered the great river as familiarly as I knew the letters of the alphabet, I had made a valuable acquisition. But I had lost something, too. I had lost something which could never be restored to me while I lived. All the grace, the beauty, the poetry had gone out of the majestic river! I still keep in mind a certain wonderful sunset which I witnessed when steamboating was new to me. A broad expanse of the river was turned to blood; in the middle distance the red hue brightened into gold, through which a solitary log came floating, black and conspicuous; in one place a long, slanting mark lay sparkling upon the water; in another the surface was broken by boiling, tumbling rings, that were as many-tinted as an opal; where the ruddy flush was faintest, was a smooth spot that was covered with graceful circles and radiating lines, ever so delicately traced; the shore on our left was densely wooded, and the somber shadow that fell from this forest was broken in one place by a long, ruffled trail that shone like silver; and high above the forest wall a clean-stemmed dead tree waved a single leafy bough that glowed like a flame in the unobstructed splendor that was flowing from the sun. There were graceful curves, reflected images, woody heights, soft distances; and over the whole scene, far and near, the dissolving lights drifted steadily, enriching it, every passing moment, with new marvels of coloring.

|

|

2Two Views of the River

I stood like one bewitched. I drank it in, in a speechless rapture. The world was new to me, and I had never seen anything like this at home. But as I have said, a day came when I began to cease from noting the glories and the charms which the moon and the sun and the twilight wrought upon the river's face; another day came when I ceased altogether to note them. Then, if that sunset scene had been repeated, I should have looked upon it without rapture, and should have commented upon it, inwardly, after this fashion: This sun means that we are going to have wind to-morrow; that floating log means that the river is rising, small thanks to it; that slanting mark on the water refers to a bluff reef which is going to kill somebody's steamboat one of these nights, if it keeps on stretching out like that; those tumbling "boils" show a dissolving bar and a changing channel there; the lines and circles in the slick water over yonder are a warning that that troublesome place is shoaling up dangerously; that silver streak in the shadow of the forest is the "break" from a new snag, and he has located himself in the very best place he could have found to fish for steamboats; that tall dead tree, with a single living branch, is not going to last long, and then how is a body ever going to get through this blind place at night without the friendly old landmark.

No, the romance and the beauty were all gone from the river. All the value any feature of it had for me now was the amount of usefulness it could furnish toward compassing the safe piloting of a steamboat. Since those days, I have pitied doctors from my heart. What does the lovely flush in a beauty's cheek mean to a doctor but a "break" that ripples above some deadly disease. Are not all her visible charms sown thick with what are to him the signs and symbols of hidden decay? Does he ever see her beauty at all, or doesn't he simply view her professionally, and comment upon her unwholesome condition all to himself? And doesn't he sometimes wonder whether he has gained most or lost most by learning his trade?

|

Now return to the Assignment 6 lecture to see how this article is used to complete Assignment 6.

ASSIGNMENT SELECTIONS

My Boyhood on the Prairie

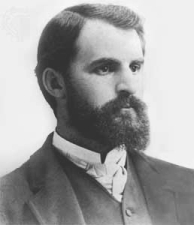

by Hamlin Garland

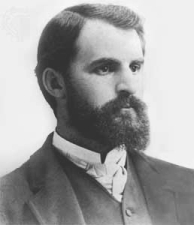

Hamlin Garland (1860-1940) was born in Wisconsin. His father was a farmer and pioneer who was always driven to live on the western edge of the farming country. As a result, Garland's family moved from Wisconsin to Minnesota, then to Iowa, and finally to the Dakota Territory. Garland's father was lured by the prospect of cheaper land, better soil, and bigger crops. Later, Hamlin Garland turned his attention to writing and decided to tell a realistic story of the western farmer's life and the great hardships, as well as the hopes and joys, of pioneer life in the Middle West. The following excerpt is set in Mitchell County, Iowa.

The excerpt below is from A Son of the Middle

Border, Hamlin Garland's autobiography first published in 1917 by the MacMillan Company in New York.

|

My Boyhood on the Prairie

by Hamlin Garland

The cabin faced a level plain with no tree in sight. A mile away to the west stood a low stone house, and immediately in front of us

opened a half-section of unfenced sod. To the north, as far as I could

see, the land billowed like a russet ocean, with scarcely a roof to

fleck its lonely spread. I cannot say that I liked or disliked it. I

merely marveled at it; and while I wandered about the yard, the hired

man scorched some cornmeal mush in a skillet, and this, with some

butter and gingerbread, made up my first breakfast in Mitchell County.

The cabin faced a level plain with no tree in sight. A mile away to the west stood a low stone house, and immediately in front of us

opened a half-section of unfenced sod. To the north, as far as I could

see, the land billowed like a russet ocean, with scarcely a roof to

fleck its lonely spread. I cannot say that I liked or disliked it. I

merely marveled at it; and while I wandered about the yard, the hired

man scorched some cornmeal mush in a skillet, and this, with some

butter and gingerbread, made up my first breakfast in Mitchell County.

For a few days my brother and I had little to do other than to

keep the cattle from straying, and we used our leisure in becoming

acquainted with the region round about.

To the south the sections were nearly all settled upon, for in that

direction lay the county town; but to the north and on into Minnesota

rolled the unplowed sod, the feeding ground of the cattle, the home of

foxes and wolves, and to the west, just beyond the highest ridges, we

loved to think the bison might still be seen.

The cabin on this rented farm was a mere shanty, a shell of pine

boards, which needed reinforcing to make it habitable, and one day my

father said, "Well, Hamlin, I guess you'll have to run the plow-team

this fall. I must help neighbor Button reinforce the house, and I

can't afford to hire another man."

|

|

2My Boyhood on the Prairie

This seemed a fine commission for a lad of ten, and I drove my horses

into the field that first morning with a manly pride which added

an inch to my stature. I took my initial "round" at a "land" which

stretched from one side of the quarter section to the other, in

confident mood. I was grown up!

But alas! My sense of elation did not last long. To guide a team for

a few minutes as an experiment was one thing--to plow all day like a

hired hand was another. It was not a chore; it was a job. It meant

moving to and fro hour after hour, day after day, with no one to

talk to but the horses. It meant trudging eight or nine miles in the

forenoon and as many more in the afternoon, with less than an hour off

at noon. It meant dragging the heavy implement around the corners, and

it meant also many shipwrecks; for the thick, wet stubble often threw

the share completely out of the ground, making it necessary for me to

halt the team and jerk the heavy plow backward for a new start.

Although strong and active, I was rather short, even for a

ten-year-old, and to reach the plow handles I was obliged to lift my

hands above my shoulders; and so with the guiding lines crossed over

my back and my worn straw hat bobbing just above the cross-brace I

must have made a comical figure. At any rate nothing like it had been

seen in the neighborhood; and the people on the road to town, looking

across the field, laughed and called to me, and neighbor Button said

to my father in my hearing, "That chap's too young to run a plow," a

judgment which pleased and flattered me greatly.

Harriet cheered me by running out occasionally to meet me as I turned

the nearest corner, and sometimes Frank consented to go all the way

around, chatting breathlessly as he trotted along behind. At other

times he brought me a cookie and a glass of milk, a deed which helped

to shorten the forenoon. And yet plowing became tedious.

|

|

3My Boyhood on the Prairie

The flies were savage, especially in the middle of the day, and the

horses, tortured by their lances, drove badly, twisting and turning in

their rage. Their tails were continually getting over the lines,

and in stopping to kick their tormentors they often got astride the

traces, and in other ways made trouble for me. Only in the early

morning or when the sun sank low at night were they able to move

quietly along their way.

The soil was the kind my father had been seeking, a smooth, dark,

sandy loam, which made it possible for a lad to do the work of a man.

Often the share would go the entire "round" without striking a root or

a pebble as big as a walnut, the steel running steadily with a crisp,

crunching, ripping sound which I rather liked to hear. In truth, the

work would have been quite tolerable had it not been so long drawn

out. Ten hours of it, even on a fine day, made about twice too many

for a boy.

Meanwhile I cheered myself in every imaginable way. I whistled. I

sang. I studied the clouds. I gnawed the beautiful red skin from the

seed vessels which hung upon the wild rose bushes, and I counted the

prairie chickens as they began to come together in winter flocks,

running through the stubble in search of food. I stopped now and again

to examine the lizards unhoused by the share, and I measured the

little granaries of wheat which the mice and gophers had deposited

deep under the ground, storehouses which the plow had violated. My

eyes dwelt enviously upon the sailing hawk and on the passing of

ducks. The occasional shadowy figure of a prairie wolf made me wish

for Uncle David and his rifle.

|

|

4My Boyhood on the Prairie

On certain days nothing could cheer me. When the bitter wind blew from

the north, and the sky was filled with wild geese racing southward

with swiftly-hurrying clouds, winter seemed about to spring upon me.

The horses' tails streamed in the wind. Flurries of snow covered me

with clinging flakes, and the mud "gummed" my boots and trouser

legs, clogging my steps. At such times I suffered from cold and

loneliness--all sense of being a man evaporated. I was just a little

boy, longing for the leisure of boyhood.

Day after day, through the month of October and deep into November,

I followed that team, turning over two acres of stubble each day. I

would not believe this without proof, but it is true! At last it grew

so cold that in the early morning everything was white with frost,

and I was obliged to put one hand in my pocket to keep it warm, while

holding the plow with the other; but I didn't mind this so much, for

it hinted at the close of autumn. I've no doubt facing the wind in

this way was excellent discipline, but I didn't think it necessary

then, and my heart was sometimes bitter and rebellious.

My father did not intend to be severe. As he had always been an

early riser and a busy toiler, it seemed perfectly natural and good

discipline that his sons should also plow and husk corn at ten years

of age. He often told of beginning life as a "bound boy" at nine, and

these stories helped me to perform my own tasks without whining.

At last there came a morning when by striking my heel upon the ground

I convinced my boss that the soil was frozen. "All right," he said;

"you may lay off this forenoon."

|

Empty Hands

by Jane Addams

Jane Addams (1860-1935) was born in Illinois in 1860 and became one of the most prominent women of her time. She was an activist working to help the poor, immigrants, child laborers, and world peace. In 1889, she founded the world-famous settlement house, Hull House, in Chicago. In 1931, she won the Nobel Peace Prize.

The excerpt comes from Addams' book Twenty Years at Hull-House, published by Macmillan, New York, in 1910. It is from Chapter IV, "The Snare of Preparation."

|

Empty Hands

by Jane Addams

The winter after I left school was spent in the Woman's Medical College of Philadelphia, but the development of the spinal difficulty which had shadowed me from childhood forced me into Dr. Weir Mitchell's hospital for the late spring, and the next winter I was literally bound to a bed in my sister's house for six months.... The long illness inevitably put aside the immediate prosecution of a medical course, and although I had passed my examinations creditably enough in the required subjects for the first year, I was very glad to have a physician's sanction for giving up clinics and dissecting rooms and to follow his prescription of spending the next two years in Europe.

The winter after I left school was spent in the Woman's Medical College of Philadelphia, but the development of the spinal difficulty which had shadowed me from childhood forced me into Dr. Weir Mitchell's hospital for the late spring, and the next winter I was literally bound to a bed in my sister's house for six months.... The long illness inevitably put aside the immediate prosecution of a medical course, and although I had passed my examinations creditably enough in the required subjects for the first year, I was very glad to have a physician's sanction for giving up clinics and dissecting rooms and to follow his prescription of spending the next two years in Europe.

Before I returned to America I had discovered that there were other genuine reasons for living among the poor than that of practicing medicine upon them, and my brief foray into the profession was never resumed.

The long illness left me in a state of nervous exhaustion with which I struggled for years, traces of it remaining long after Hull-House was opened in 1889. At the best it allowed me but a limited amount of energy, so that doubtless there was much nervous depression at the foundation of the spiritual struggles which this chapter is forced to record....

It would, of course, be impossible to remember that some of these struggles ever took place at all, were it not for these selfsame notebooks, in which, however, I no longer wrote in moments of high resolve, but judging from the internal evidence afforded by the books themselves, only in moments of deep depression when overwhelmed by a sense of failure.

|

|

2Empty Hands

One of the most poignant of these experiences, which occurred during the first few months after our landing upon the other side of the Atlantic, was on a Saturday night, when I received an ineradicable impression of the wretchedness of East London, and also saw for the first time the overcrowded quarters of a great city at midnight. A small party of tourists were taken to the East End by a city missionary to witness the Saturday night sale of decaying vegetables and fruit, which, owing to the Sunday laws in London, could not be sold until Monday, and, as they were beyond safe keeping, were disposed of at auction as late as possible on Saturday night.

On Mile End Road, from the top of an omnibus which paused at the end of a dingy street lighted by only occasional flares of gas, we saw two huge masses of ill-clad people clamoring around two hucksters' carts. They were bidding their farthings and ha'pennies for a vegetable held up by the auctioneer, which he at last scornfully flung, with a gibe for its cheapness, to the successful bidder. In the momentary pause only one man detached himself from the groups. He had bidden on a cabbage, and when it struck his hand, he instantly sat down on the curb, tore it with his teeth, and hastily devoured it, unwashed and uncooked as it was.

He and his fellows were types of the "submerged tenth," as our missionary guide told us, with some little satisfaction in the then new phrase, and he further added that so many of them could scarcely be seen in one spot save at this Saturday night auction, the desire for cheap food being apparently the one thing which could move them simultaneously. They were huddled into ill-fitting, cast-off clothing, the ragged finery which one sees only in East London. Their pale faces were dominated by that most unlovely of human expressions, the cunning and shrewdness of the bargain-hunter who starves if he cannot make a successful trade, and yet the final impression was not of ragged, tawdry clothing nor of pinched and sallow faces, but of myriads of hands, empty, pathetic, nerveless and workworn, showing white in the uncertain light of the street, and clutching forward for food which was already unfit to eat.

|

|

3Empty Hands

Perhaps nothing is so fraught with significance as the human hand, this oldest tool with which man has dug his way from savagery, and with which he is constantly groping forward. I have never since been able to see a number of hands held upward, even when they are moving rhythmically in a calisthenic exercise, or when they belong to a class of chubby children who wave them in eager response to a teacher's query, without a certain revival of this memory, a clutching at the heart reminiscent of the despair and resentment which seized me then.

For the following weeks I went about London almost furtively, afraid to look down narrow streets and alleys lest they disclose again this hideous human need and suffering. I carried with me for days at a time that curious surprise we experience when we first come back into the streets after days given over to sorrow and death; we are bewildered that the world should be going on as usual and unable to determine which is real, the inner pang or the outward seeming. In time all huge London came to seem unreal save the poverty in its East End.

During the following two years on the continent, while I was irresistibly drawn to the poorer quarters of each city, nothing among the beggars of South Italy nor among the salt miners of Austria carried with it the same conviction of human wretchedness which was conveyed by this momentary glimpse of an East London street. It was, of course, a most fragmentary and lurid view of the poverty of East London, and quite unfair. I should have been shown either less or more, for I went away with no notion of the hundreds of men and women who had gallantly identified their fortunes with these empty-handed people, and who, in church and chapel, "relief works," and charities, were at least making an effort towards its mitigation.

|

Race Evils

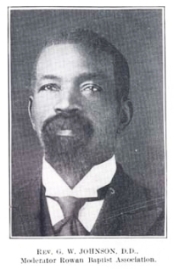

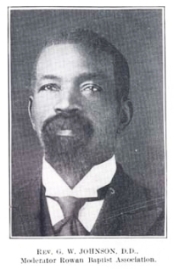

by Reverend G.W. Johnson

Reverend G.W. Johnson (1856-?) was a popular Southern Baptist minister. His views were clear, but they were not universally accepted by his parishioners. Johnson helped found several churches, and in 1908 he received a Doctor of Divinity degree from Guadaloupe College in Seguin, Texas.

The sermon comes from Sparkling Gems of Race Knowledge Worth Reading: A Compendium of Valuable Information and Wise Suggestions That Will Inspire Noble Effort at the Hands of Every Race-Loving Man, Woman, and Child. The book was published by J. T. Haley & Company, Publishers, in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1897.

The photo comes from A History of the Negro Baptists of North Carolina, edited by J. A. Whitted and published by Edwards & Broughton Printing Co., in Raleigh in 1908.

|

Race Evils

by Reverend G.W. Johnson

One trouble with us as a race is that we are not enough interested in our progress, not enough interested in our standing among other races. We are too easily satisfied, and not very anxious to get far away from the fleshpots of Egypt. Every race must have its leaders, defenders, and champions. If they have them not, they must produce them.

One trouble with us as a race is that we are not enough interested in our progress, not enough interested in our standing among other races. We are too easily satisfied, and not very anxious to get far away from the fleshpots of Egypt. Every race must have its leaders, defenders, and champions. If they have them not, they must produce them.

We should begin with childhood. Every criminal was once an innocent child, and when he first commenced to do wrong, he found it hard and difficult. Conscience called, alarmed, and remonstrated; and even after wrongs were committed, conscience, the interior judge, held court on the inside. He arraigned the prisoner at the bar of reason for trial; but he continues to do wrong, and in early manhood he stands a criminal. Step by step he was led away.

Take the murderer. He occupies his cell hardened by crime. Sentence has been passed; the day of execution comes. The sheriff enters the prison, reads the death warrant, pinions his hands, and the slow and steady death march begins. The scaffold is reached, steps ascended, and the prisoner takes his place on the center of the death trap; the black cap is securely tied over his face, and the rope around his neck, and as the trapdoor is sprung, the unfortunate man leaps into darkness. This criminal was once the idol of a mother's heart, who bowed over his cradle, taught him to walk and to say his prayers. She looked forward to the time when he would grow up to manhood and make himself felt among the world's great men; but alas! those hopes are blighted. The boy begins the downward way keeping bad company, and staying out late at night. He associates with gamblers and drunkards, and soon becomes both. He goes to jail, to the chain gang, to the penitentiary, and finally to the gallows. Much of the dishonesty is due to the negligence of parents in early training.

|

|

2Race Evils

I want to call your attention to that craze for fine dressing. If parents would teach their daughters that a beautiful character is the best and greatest ornament, and that a pure heart beneath the most common costume is to be prized above silk and satin at the price of virtue, we would have a better and purer race.

We have many enemies of the race who are members of the race. I will call your attention to them by classes.

We have a class of women who boast of their association with white men, and yet demand honor and respect from men of the race. Some of our churches have been so loose as to give them membership, and every now and then some fool Negro man will marry one. This class of women hinders the progress of the race, and is indeed a curse to it, and many of the white men who seek to lead astray every good-looking woman in our race frequently refer to the immorality of colored women. The race must frown upon this class of women, and make them feel their isolation at all hazards. They should be treated as the lepers were and are treated in the East to-day—put off to themselves; and all who associate with them should be pronounced unclean.

The next class is the professional pimps. This class is represented by a number of men and women who make a business of leading astray every girl they can, disregarding their destruction and the sorrow brought to the hearts of parents and friends, the disgrace to the race, just since they receive some money for their hellish work. Some of these professional pimps are members of some of our churches, I am told. I would suggest that every father and mother, and every man who has a sister, resolve to make it extremely hot for this class of the devil's agents. Hand them around; blackball them; sound the alarm of mad dog. Get them out of the church; have no association with them. Keep your daughters from about them. Greet them as you would the devil, for they are devils wrapped up in human flesh. I warn you against these men and women who carry notes to girls for white men, and who lay snares for the destruction of our girls. Have nothing to do with them.

|

|

3Race Evils

The next class among our race that is a hindrance and a barrier is represented by a number of men. These men seem to regard themselves called to win the affections of light-headed and light-hearted girls, get engaged to them, and after destroying their characters betake themselves to others for marriage. The man who destroys the character of a woman has as much right to be put aside and excluded from society as the woman, and that society which recognizes such a man, and yet ignores the woman, is rotten and demoralizing. We can never purify society until we have good men as well as good women. We have too many men in our race who delight to speak disreputably of nearly every woman when they themselves have a very unsavory reputation, and should be regarded with great diffidence. There are many women in our race who are just as pure, and whose characters are just as irreproachable as the women of any race, and our men owe it to these women and to the race the duty of defending and protecting them, even to the risk of our own lives. We should always speak of them in complimentary terms, and allow no one to speak otherwise in our presence without positive resentment.

The next class I want to discuss is the idle, lazy, shiftless, vagrant class. The class I refer to are those who will not work, and yet hate every man and woman who will labor and strive to accumulate something. As a race, we are too jealous and grudgeful of each other's success and prosperity. The prophet in his vision saw the image of jealousy set up. In lifting the veil of futurity he must have seen the condition of the Negro in the closing years of the nineteenth century. Our children must be taught to work, and to love work. They must be taught that work is honorable. The working people of any community are the mainstay and backbone of that community. Paul said: "If any would not work, neither should he eat."

Christ, our glorious example, was a working man, the carpenter of Nazareth, a busy man, a man distinctively of the common people. Christ did not have among his disciples a single gentleman of leisure. They were all working men. In the early history of the church the great majority of believers were from among the working people. Peter, Andrew, James, and John were fishermen; Paul was a tent-maker; Moses, the greatest human legislator the world ever produced, was once a shepherd; Elisha was a farmer, and was called from the plow to succeed Elijah. Joseph and Daniel were servants before they were made prime ministers. Martin Luther was a miner's son. Cardinal Wolsey was the son of a butcher. John Bunyan was a tinker. William Carey was a shoemaker. Jeremy Taylor was a barber. Dr. Livingstone was a weaver. Every man ought to engage in some kind of work, either braincraft or handicraft.

|

San Antonio, 1841

by Mary A. Maverick

Mary Ann Adams Maverick (1818-1898) was a famous Texas pioneer and diarist. Born in Alabama, she married Samuel A. Maverick in 1836. Samuel Maverick had been educated at Yale, had fought in the Texas Revolution, had acquired large areas of land in Texas, and had his name pass into the common vernacular to describe an orphaned calf. Mary and Samuel Maverick moved to Texas in 1838 and witnessed the tumultuous growth of the country. In 1880, Mary recalled her life experiences in The Memoirs of Mary A. Maverick, a marvelous chronicle of her association with many of the early leaders of Texas and a touching recount of her many personal tragedies, especially the loss of four of her ten children. Mary Maverick's mother, mentioned in the excerpt, lived in Alabama.

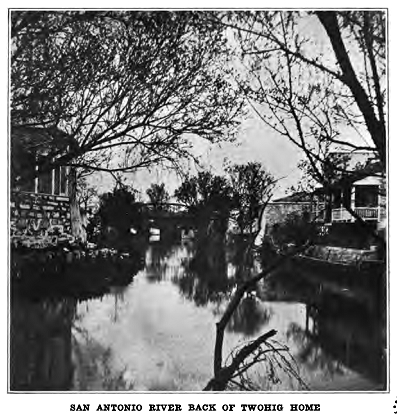

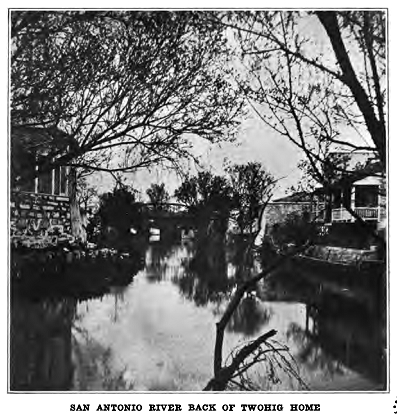

As noted, Mary Maverick wrote her memoirs in 1880. This excerpt is from Chapter IX of the 1921 publication of those memoirs. The memoirs were published by Alamo Printing Company in San Antonio. The photos are from that 1921 publication.

|

San Antonio, 1841

by Mary A. Maverick

Easter Monday, April 12th, 1841, Agatha, our first daughter was born and named for my mother. She was a very beautiful and good baby.

Easter Monday, April 12th, 1841, Agatha, our first daughter was born and named for my mother. She was a very beautiful and good baby.

My mother talked of coming out to visit us. Her idea was that she would come to some port on the coast, and

we would go down at the appointed time and meet her

there. But I had too many babies to make such a journey,

and the risk from Indians was too great, and we did not

encourage the plan. Her letters were one month to six

weeks old when we received them.

President Lamar with a very considerable suite visited

San Antonio in June. A grand ball was given him in Mrs.

Yturri's long room—all considerable houses had a long

room for receptions. The room was decorated with flags

and evergreens; flowers were not much cultivated then. At the ball, General Lamar wore very wide white pants

which at the same time were short enough to show the

tops of his shoes. General Lamar and Mrs. Juan N. Seguin, wife of the Mayor, opened the ball with a waltz.

Mrs. Seguin was so fat that the General had great difficulty in getting a firm hold on her waist, and they cut such a figure that we were forced to smile. The General was a poet, a polite and brave gentleman and first rate conversationalist—but he did not dance well.

|

|

2San Antonio, 1841

At the ball, Hays, Chevalier, and John Howard had but

one dress coat between them, and they agreed to use the

coat and dance in turn. The two not dancing would stand at the hall door watching the happy one who was enjoying his turn—and they reminded him when it was time

for him to step out of that coat. Great fun was it watching them and listening to their wit and mischief as they

made faces and shook their fists at the dancing one.

John D. Morris, the Adonis of the company, escorted

Miss Arceneiga who on that warm evening wore a maroon

cashmere with black plumes in her hair, and her haughty

airs did not gain her any friends. Mrs. Yturri had a new

silk, fitting her so tightly that she had to wear corsets for

the first time in her life. She was very pretty, waltzed

beautifully and was much sought as a partner. She was

several times compelled to escape to her bedroom to take

off the corset and "catch her breath" as she said to me

who happened to be there with my baby.

By the way, speaking of Mrs. Yturri, I am reminded of

a party I gave several months before this. It blew a

freezing norther that day and we had the excellent good

luck of making some ice cream, which was a grateful surprise to our guests. In fact, those of the Mexicans present,

who had never travelled, tasted ice cream that evening

for the first time in their lives, and they all admired and

liked it. But Mrs. Yturri ate so much of it, tho' advised

not to, that she was taken with cramps. Mrs. Jacques

and I took her to my room and gave her brandy, but in

vain, and she had to be carried home. At that party

some natives remained so late in the morning that we had

to ask them to go. One man of reputable standing carried

off a roast chicken in his pocket, another a carving knife,

and several others took off all the cake they could well

conceal, which greatly disgusted Jinny Anderson, the

cook. Griffin followed the man with the carving knife

and took it away from him.

During this summer, the American ladies led a lazy

life of ease. We had plenty of books, including novels,

we were all young, healthy and happy and were content with each others' society. We fell into the fashion of the

climate, dined at twelve, then followed a siesta (nap)

until three, when we took a cup of coffee and a bath.

|

|

3San Antonio, 1841

Bathing in the river at our place had become rather

public, now that merchants were establishing themselves

on Commerce Street, so we ladies got permission of old

Madame Tevino, mother of Mrs. Lockmar, to put up a

bath house on her premises, some distance up the river on

Soledad Street, afterwards the property and homestead

of the Jacques family. Here between two trees in a

beautiful shade, we went in a crowd each afternoon at

about four o'c1ock and took the children and nurses and

a nice lunch which we enjoyed after the bath. There we

had a grand good time, swimming and laughing, and

making all the noise we pleased.

The children were

bathed and after all were dressed, we spread our lunch

and enjoyed it immensely. The ladies took turns in preparing the lunch and my aunt Mrs. Bradley took the lead

in nice things. Then we had a grand and glorious gossip,

for we were all dear friends and each one told the news

from our far away homes in the "States," nor did we omit

to review the happenings in San Antonio. We joked and

laughed away the time, for we were free from care and

happy. In those days there were no envyings, no back-biting.

|

|

4San Antonio, 1841

In September mother wrote she had determined to visit us, that she would leave Robert and Lizzie at school and

that George would accompany her. William and Andrew

were then on the San Marcos. She wrote she would set

out about October first, and should she like our town she

would sell out in Tuskaloosa and move to San Antonio.

That letter arrived late in October, and soon after it came

a letter from Professor Wilson to Mr. Maverick, and a letter from Mrs. Snow to me telling us that my dear

mother was no more. She was taken with congestive

chills—the first had been severe, but the second was light, and two weeks having elapsed after the second chill, Dr. Weir, her physician, considered her out of danger from a third.

Lizzie had come home from school, and slept in the adjoining room, and a servant girl much attached to

my mother slept on a pallet before mother's door. Mother

would not allow any one to sit up with her now, and her tonic, lamp and watch were placed on a table near her.

A third chill must have come on during the night, for by

the early morning light, on October 2nd, they found that

my dear mother was cold and dead. Oh, what a grief to

me was this first great loss of my life. Her heart had

been so set upon seeing me that I now blamed myself for

not going to meet her at the coast when she had proposed

it.

My mother had a sorrowful widowed life, for she was

not always successful in managing business or in governing her boys. She blamed herself for her want of success

as she called it, and she seldom smiled and never appeared to enjoy life. She was a devoted mother, but probably

too strict with her children, and she was an humble, faithful Christian. Her death was to me a sudden awakening

from a fancied security against all possible evil. Slowly

and sadly I came to realize that my dear mother had left

this world forever, and we should not meet again on

earth.

|

Hunting the American Buffalo

by Theodore Roosevelt

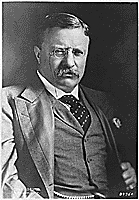

Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), the 26th President of the United States, was born in New York City. He was a frail boy, but he overcame his frailty by regular exercise and outdoor life. He was always interested in animals and especially in hunting game in the American West. He was instrumental in establishing the national park system. He recorded his western experiences in The Deer Family, Hunting the Grizzly and Other Sketches, and The Wilderness Hunter.

The following excerpt comes from The Wilderness Hunter and was reprinted in 1909 in The Elson Grammar School Reader, edited by William H. Elson and Christine M. Keck. In the early 1930s, William Elson created the iconic "Fun with Dick and Jane" beginning reading series.

|

Hunting the American Buffalo

by Theodore Roosevelt

In the fall of 1889 I heard that a very few bison were still left around the head of Wisdom River. Thither I went and hunted faithfully; there was plenty of game of other kinds, but of bison not a trace did we see. Nevertheless, a few days later that same year I came across these great wild cattle at a time when I had no idea of seeing them.

In the fall of 1889 I heard that a very few bison were still left around the head of Wisdom River. Thither I went and hunted faithfully; there was plenty of game of other kinds, but of bison not a trace did we see. Nevertheless, a few days later that same year I came across these great wild cattle at a time when I had no idea of seeing them.

It was, as nearly as we could tell, in Idaho, just south of the Montana boundary line, and some twenty-five miles west of the line of Wyoming. We were camped high among the mountains, with a small pack train. On the day in question we had gone out to find moose, but had seen no sign of them, and had then begun to climb over the higher peaks with an idea of getting sheep. The old hunter who was with me was, very fortunately, suffering from rheumatism, and he therefore carried a long staff instead of his rifle; I say fortunately, for if he had carried his rifle, it would have been impossible to stop his firing at such game as bison, nor would he have spared the cows and calves.

About the middle of the afternoon we crossed a low, rocky ridge, and saw at our feet a basin, or round valley, of singular beauty. Its walls were formed by steep mountains. At its upper end lay a small lake, bordered on one side by a meadow of emerald green. The lake's other side marked the edge of the frowning pine forest which filled the rest of the valley. Beyond the lake the ground rose in a pass much frequented by game in bygone days, their trails lying along it in thick zigzags, each gradually fading out after a few hundred yards, and then starting again in a little different place, as game trails so often seem to do.

|

|

2Hunting the American Buffalo

We bent our steps toward these trails, and no sooner had we reached the first than the old hunter bent over it with a sharp exclamation of wonder. There in the dust, apparently but a few hours old, were the hoof-marks of a small band of bison. They were headed toward the lake. There had been half a dozen animals in the party; one a big bull, and two calves.

We immediately turned and followed the trail. It led down to the little lake, where the beasts had spread and grazed on the tender, green blades, and had drunk their fill. The footprints then came together again, showing where the animals had gathered and walked off in single file to the forest. Evidently they had come to the pool in the early morning, and after drinking and feeding had moved into the forest to find some spot for their noontide rest.

It was a very still day, and there were nearly three hours of daylight left. Without a word my silent companion, who had been scanning the whole country with hawk-eyed eagerness, took the trail, motioning me to follow. In a moment we entered the woods, breathing a sigh of relief as we did so; for while in the meadow we could never tell that the buffalo might not see us, if they happened to be lying in some place with a commanding lookout.

It was not very long before we struck the day-beds, which were made on a knoll, where the forest was open, and where there was much down timber. After leaving the day-beds the animals had at first fed separately around the grassy base and sides of the knoll, and had then made off in their usual single file, going straight to a small pool in the forest. After drinking they had left this pool and traveled down toward the mouth of the basin, the trail leading along the sides of the steep hill, which were dotted by open glades. Here we moved with caution, for the sign had grown very fresh, and the animals had once more scattered and begun feeding. When the trail led across the glades, we usually skirted them so as to keep in the timber.

|

|

3Hunting the American Buffalo

At last, on nearing the edge of one of these glades, we saw a movement among the young trees on the other side, not fifty yards away. Peering through some thick evergreen bushes, we speedily made out three bison, a cow, a calf, and a yearling, grazing greedily on the other side of the glade. Soon another cow and calf stepped out after them. I did not wish to shoot, waiting for the appearance of the big bull which I knew was accompanying them.

So for several minutes I watched the great, clumsy, shaggy beasts, as they grazed in the open glade. Mixed with the eager excitement of the hunter was a certain half-melancholy feeling as I gazed on these bison, themselves part of the last remnant of a nearly vanished race. Few, indeed, are the men who now have, or evermore shall have, the chance of seeing the mightiest of American beasts in all his wild vigor.

At last, when I had begun to grow very anxious lest the others should take alarm, the bull likewise appeared on the edge of the glade, and stood with outstretched head, scratching his throat against a young tree, which shook violently. I aimed low, behind his shoulder, and pulled the trigger. At the crack of the rifle all the bison turned and raced off at headlong speed. The fringe of young pines beyond and below the glade cracked and swayed as if a whirlwind were passing, and in another moment the bison reached the top of a steep incline, thickly strewn with boulders and dead reckless speed; the timber. Down this they plunged with surefootedness that was a marvel. A column of dust obscured their passage, and under its cover they disappeared in the forest; but the trail of the bull was marked by splashes of frothy blood, and we followed it at a trot. Fifty yards beyond the border of the forest we found the black body stretched motionless. He was a splendid old bull, still in his full vigor, with large, sharp horns, and heavy mane and glossy coat; and I felt the most exulting pride as I handled and examined him; for I had procured a trophy such as can fall henceforth to few hunters indeed.

|

Black Hawk's Surrender Speech

by Black Hawk

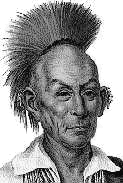

In 1832, after a treaty dispute, Black Hawk led a group of Sauk Indians back from the Iowa territory to their homes in Illinois. Though these Indians were causing no trouble, white people panicked, and soldiers were sent out to deal with Black Hawk. One of the soldiers in what came to be known as the Black Hawk War was young Abraham Lincoln.

Several skirmishes occurred between the two forces. The last occurred near the Mississippi River in the Wisconsin area. In the Bad Axe Massacre, soldiers killed many Sauk Indians--women, children, and the old included. Some of the Sauk escaped across the Mississippi River, but there they were attacked by Sioux Indians who had sided with the soldiers. Of the 500 Sauk who had traveled with Black Hawk, only 150 survived. The Black Hawk War claimed the lives of about 70 white people and about 500 American Indians.

Black Hawk was a survivor of the massacre. He surrendered and was sent to the eastern United States. There, he was paraded through the streets like a captive animal. Curiously, the public had the reverse reaction and treated Black Hawk as a hero. Black Hawk's speech is included in Biography and History of the Indians of North America, by Samuel G. Drake, published in Boston in 1841.

|

Black Hawk's Surrender Speech

by Black Hawk

You have taken me prisoner with all my warriors. I am much grieved, for I expected, if I did not defeat you, to hold out much longer, and give you more trouble before I surrendered. I tried hard to bring you into ambush, but your last general understands Indian fighting. The first one was not so wise. When I saw that I could not beat you by Indian fighting, I determined to rush on you, and fight you face to face. I fought hard. But your guns were well aimed. The bullets flew like birds in the air, and whizzed by our ears like the wind through the trees in the winter. My warriors fell around me; it began to look dismal. I saw my evil day at hand. The sun rose dim on us in the morning, and at night it sunk in a dark cloud, and looked like a ball of fire.

You have taken me prisoner with all my warriors. I am much grieved, for I expected, if I did not defeat you, to hold out much longer, and give you more trouble before I surrendered. I tried hard to bring you into ambush, but your last general understands Indian fighting. The first one was not so wise. When I saw that I could not beat you by Indian fighting, I determined to rush on you, and fight you face to face. I fought hard. But your guns were well aimed. The bullets flew like birds in the air, and whizzed by our ears like the wind through the trees in the winter. My warriors fell around me; it began to look dismal. I saw my evil day at hand. The sun rose dim on us in the morning, and at night it sunk in a dark cloud, and looked like a ball of fire.

That was the last sun that shone on Black Hawk. His heart is dead, and no longer beats quick in his bosom. He is now a prisoner to the white men; they will do with him as they wish. But he can stand torture, and is not afraid of death. He is no coward. Black Hawk is an Indian.

He has done nothing for which an Indian ought to be ashamed. He has fought for his countrymen, the squaws and papooses, against white men, who came, year after year, to cheat them and take away their lands. You know the cause of our making war. It is known to all white men. They ought to be ashamed of it. The white men despise the Indians, and drive them from their homes. But the Indians are not deceitful. The white men speak bad of the Indian, and look at him spitefully. But the Indian does not tell lies; Indians do not steal.

|

|

2Black Hawk's Surrender Speech

An Indian who is as bad as the white men, could not live in our nation; he would be put to death, and eat up by the wolves. The white men are bad school-masters; they carry false looks, and deal in false actions; they smile in the face of the poor Indian to cheat him; they shake them by the hand to gain their confidence, to make them drunk, to deceive them, and ruin our wives. We told them to let us alone; but they followed on and beset our paths, and they coiled themselves among us like the snake. They poisoned us by their touch. We were not safe. We lived in danger. We were becoming like them, hypocrites and liars, adulterers, lazy drones, all talkers, and no workers.

We looked up to the Great Spirit. We went to our great father. We were encouraged. His great council gave us fair words and big promises, but we got no satisfaction. Things were growing worse. There were no deer in the forest. The oppossum and beaver were fled; the springs were drying up, and our squaws and papooses without victuals to keep them from starving; we called a great council and built a large fire. The spirit of our fathers arose and spoke to us to avenge our wrongs or die. . . . We set up the war-whoop, and dug up the tomahawk; our knives were ready, and the heart of Black Hawk swelled high in his bosom when he led his warriors to battle. He is satisfied. He will go to the world of spirits contented. He has done his duty. His father will meet him there, and commend him.

Black Hawk is a true Indian, and disdains to cry like a woman. He feels for his wife, his children and friends. But he does not care for himself. He cares for his nation and the Indians. They will suffer. He laments their fate. The white men do not scalp the head; but they do worse—they poison the heart, it is not pure with them. His countrymen will not be scalped, but they will, in a few years, become like the white men, so that you can't trust them, and there must be, as in the white settlements, nearly as many officers as men, to take care of them and keep them in order.

Farewell, my nation. Black Hawk tried to save you, and avenge your wrongs. He drank the blood of some of the whites. He has been taken prisoner, and his plans are stopped. He can do no more. He is near his end. His sun is setting, and he will rise no more. Farewell to Black Hawk.

|

The Story of an Eyewitness

by Jack London

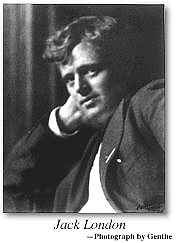

John Griffith (Jack) London (1876-1916) was a famous American novelist who was born in San Francisco and later settled in Oakland. He is best known for his novels about the Yukon Gold Rush (Call of the Wild, White Fang), though during his short life he wrote over fifty volumes of novels, stories, and political essays. He died of kidney failure in 1916.

On Wednesday, April 18, 1906, a devastating earthquake struck San Francisco. Because London lived nearby, Collier's Magazine commissioned him to go into the city and write an eyewitness report. London went into the ruined city immediately, and the following excerpt is about half of his original report. London's report was first published in Collier's Magazine, May 5, 1906. The photos were not in the original article.

If you choose this selection for your Assignment 6 analysis, you should first review the Purposes and Patterns Primer: Referential Purpose section very thoroughly.

The Story of an Eyewitness

by Jack London

THE earthquake shook down in San Francisco hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of walls and chimneys. But the conflagration that followed burned up hundreds of millions of dollars' worth of property. There is no estimating within hundreds of millions the actual damage wrought. Not in history has a modern imperial city been so completely destroyed. San Francisco is gone. Nothing remains of it but memories and a fringe of dwelling-houses on its outskirts. Its industrial section is wiped out. Its business section is wiped out. Its social and residential section is wiped out. The factories and warehouses, the great stores and newspaper buildings, the hotels and the palaces of the nabobs, are all gone. Remains only the fringe of dwelling houses on the outskirts of what was once San Francisco.

Within an hour after the earthquake shock the smoke of San Francisco's burning was a lurid tower visible a hundred miles away. And for three days and nights this lurid tower swayed in the sky, reddening the sun, darkening the day, and filling the land with smoke.

On Wednesday morning at a quarter past five came the earthquake. A minute later the flames were leaping upward. In a dozen different quarters south of Market Street, in the working-class ghetto, and in the factories, fires started. There was no opposing the flames. There was no organization, no communication. All the cunning adjustments of a twentieth century city had been smashed by the earthquake. The streets were humped into ridges and depressions, and piled with the debris of fallen walls. The steel rails were twisted into perpendicular and horizontal angles. The telephone and telegraph systems were disrupted. And the great water-mains had burst. All the shrewd contrivances and safeguards of man had been thrown out of gear by thirty seconds' twitching of the earth-crust.

|

|

2The Story of an Eyewitness

The Fire Made its Own Draft

By Wednesday afternoon, inside of twelve hours, half the heart of the city was gone. At that time I watched the vast conflagration from out on the bay. It was dead calm. Not a flicker of wind stirred. Yet from every side wind was pouring in upon the city. East, west, north, and south, strong winds were blowing upon the doomed city. The heated air rising made an enormous suck. Thus did the fire of itself build its own colossal chimney through the atmosphere. Day and night this dead calm continued, and yet, near to the flames, the wind was often half a gale, so mighty was the suck.

Wednesday night saw the destruction of the very heart of the city. Dynamite was lavishly used, and many of San Francisco's proudest structures were crumbled by man himself into ruins, but there was no withstanding the onrush of the flames. Time and again successful stands were made by the fire-fighters, and every time the flames flanked around on either side or came up from the rear, and turned to defeat the hard-won victory.

Before the flames, throughout the night, fled tens of thousands of homeless ones. Some were wrapped in blankets. Others carried bundles of bedding and dear household treasures. Sometimes a whole family was harnessed to a carriage or delivery wagon that was weighted down with their possessions. Baby buggies, toy wagons, and go-carts were used as trucks, while every other person was dragging a trunk. Yet everybody was gracious. There was no shouting and yelling. There was no hysteria, no disorder. The most perfect courtesy obtained. Never in all San Francisco's history, were her people so kind and courteous as on this night of terror.

|

|

3The Story of an Eyewitness

A Caravan of Trunks

All night these tens of thousands fled before the flames. Many of them, the poor people from the labor ghetto, had fled all day as well. They had left their homes burdened with possessions. Now and again they lightened up, flinging out upon the street clothing and treasures they had dragged for miles.

They held on longest to their trunks, and over these trunks many a strong man broke his heart that night. The hills of San Francisco are steep, and up these hills, mile after mile, were the trunks dragged. Everywhere were trunks with across them lying their exhausted owners, men and women. Before the march of the flames were flung picket lines of soldiers. And a block at a time, as the flames advanced, these pickets retreated. One of their tasks was to keep the trunk-pullers moving. The exhausted creatures, stirred on by the menace of bayonets, would arise and struggle up the steep pavements, pausing from weakness every five or ten feet.

Often, after surmounting a heart-breaking hill, they would find another wall of flame advancing upon them at right angles and be compelled to change anew the line of their retreat. In the end, completely played out, after toiling for a dozen hours like giants, thousands of them were compelled to abandon their trunks. Here the shopkeepers and soft members of the middle class were at a disadvantage. But the working-men dug holes in vacant lots and backyards and buried their trunks.

|

|

4The Story of an Eyewitness

The Doomed City

At nine o'clock Wednesday evening I walked down through the very heart of the city. I walked through miles and miles of magnificent buildings and towering skyscrapers. Here was no fire. All was in perfect order. The police patrolled the streets. Every building had its watchman at the door. And yet it was doomed, all of it. There was no water. The dynamite was giving out. And at right angles two different conflagrations were sweeping down upon it.

At one o'clock in the morning I walked down through the same section. Everything still stood intact. There was no fire. And yet there was a change. A rain of ashes was falling. The watchmen at the doors were gone. The police had been withdrawn. There were no firemen, no fire-engines, no men fighting with dynamite. The district had been absolutely abandoned. I stood at the corner of Kearney and Market, in the very innermost heart of San Francisco. Kearny Street was deserted. Half a dozen blocks away it was burning on both sides. The street was a wall of flame. And against this wall of flame, silhouetted sharply, were two United States cavalrymen sitting their horses, calming watching. That was all. Not another person was in sight. In the intact heart of the city two troopers sat their horses and watched.

|

|

5The Story of an Eyewitness

Spread of the Conflagration

Surrender was complete. There was no water. The sewers had long since been pumped dry. There was no dynamite. Another fire had broken out further uptown, and now from three sides conflagrations were sweeping down. The fourth side had been burned earlier in the day. In that direction stood the tottering walls of the Examiner building, the burned-out Call building, the smoldering ruins of the Grand Hotel, and the gutted, devastated, dynamited Palace Hotel.

The following will illustrate the sweep of the flames and the inability of men to calculate their spread. At eight o'clock Wednesday evening I passed through Union Square. It was packed with refugees. Thousands of them had gone to bed on the grass. Government tents had been set up, supper was being cooked, and the refugees were lining up for free meals

At half past one in the morning three sides of Union Square were in flames. The fourth side, where stood the great St. Francis Hotel was still holding out. An hour later, ignited from top and sides the St. Francis was flaming heavenward. Union Square, heaped high with mountains of trunks, was deserted. Troops, refugees, and all had retreated.

|

Austin, 1861

by Amelia Edith Barr

Amelia Edith Huddleston Barr (1831-1919) was born in England and married Robert Barr, a Scottish accountant in 1850. Soon after, the couple sailed to America, settling first in New York City, then Chicago, and finally Austin in 1856, where Mr. Barr worked as an auditor for the state government. The Barrs left Austin in 1866. During her time in Austin, Mrs. Barr chronicled the events and changes in the city.

In 1913, she published her life's story in All the Days of My Life: an autobiography. The book was published in 1913 in New York City by D. Appleton and Company. The excerpt below is from Chapter 14 of the autobiography, entitled "The Beginning of Strife." You can find more information about Mrs. Barr and her husband in the Handbook of Texas Online. You can find her autobiography at Google Books. The photo is from online-literature.com.

Austin, 1861

by Amelia Edith Barr

On April the fifteenth, 1861, my daughter Ethel was born. She was the loveliest babe I ever saw, and I was so proud of her beauty, I could hardly bear her out of my sight. Before she was two months old, she showed every sign of a loving and joyous disposition. If I came into the room she stretched out her arms to me; if I took her to my breast she reached up her hand to my mouth to be kissed. She smiled and loved every hour away, and the whole household delighted in her. Robert could refuse her nothing; no matter how busy he was, if she sought his attention, he left all and took her in his arms. I forgot the war, I forgot all my anxieties, I let the negroes take their own way, I was content for many weeks to nurse my lovely child, and dream of the grand future she was sure to have.

Yet during this apparently peaceful pause in my life, the changes I feared were taking place. The new Governor was dismissing as far as he could all Houston's friends, and Robert had been advised to resign before his sentiments concerning slavery, state rights, and his own citizenship came to question. . . .

The summer came on hot and early, and was accompanied by a great drought. Pitiful tales came into town of the suffering for water at outlying farms, the creeks having dried up, and even the larger rivers showing great depletion. Then the cattle and game began to die of thirst, and of some awful disease called "black tongue." Thousands lay dead upon the prairies, which were full of deep and wide fissures, made by the cracking and parting of the hot, dry earth.

|

|

2Austin, 1861

The suffering so close at hand made me indifferent to what was going on at a distance, and also all through that long, terrible summer, I was aware that Robert was practicing a very strict personal economy. So I was sure that he was not making as much money as he expected to make, and when he asked me, one day, if I could manage with two servants, I was prepared to answer, "Dear, I can do with one, if it is necessary." And I was troubled when he thankfully accepted my offer.

To be poor! That was a condition I had never considered, so I thought it over. We could never want food in Texas, unless the enemy should drive his cannon wheels over our prairies, and make our old pine woods wink with bayonets. Then, indeed, the corn and the wheat and the cattle might be insufficient for us and for them, but this event seemed far off, and unlikely. Our clothing was in far less plentiful case. My own once abundant wardrobe was considerably worn and lessened. Robert's had suffered the same change, and the children's garments wanted a constant replacing. But then, every one was in the same condition; we should be no poorer than others. A poverty that is universal may be cheerfully borne; it is an individual poverty that is painful and humiliating.

Slowly, so slowly, the hot blistering summer passed away. It was all I could do, to look a little after my five children. I dressed myself and them in the coolest manner, and the younger ones refused anything like shoes and stockings; but that was a common fashion for Texan children in hot weather. I have seen them step from handsome carriages barefooted, and envied them. People must live day after day where the thermometer basks anywhere between 105 degrees and 115 degrees, to know what a luxury naked feet are—nay, what a necessity for a large part of the time.

|

|

3Austin, 1861

Not a drop of rain had fallen for many weeks, and, when the drought was broken, it was by a violent storm. It came up unexpectedly one clear, hot afternoon, when all the world seemed to stand still. The children could not play. I had laid Ethel in her cot, and was sitting motionless beside her. The negroes in the kitchen were sleeping instead of quarreling, and, though Robert and I exchanged a weary smile occasionally, it was far too hot to talk.

Suddenly, the sky changed from blue to red, to slate color, and then to a dense blackness, even to the zenith. The heavens seemed about to plunge down upon the earth, and the air became so tenuous, that we sighed as men do, on the top of a high mountain. Then on the horizon there appeared a narrow, brassy zone, and it widened and widened, as it grew upward, and with it came the fierce rush and moan of mighty winds, slinging hail-stones and great rain-drops, from far heights—swaying, pelting, rushing masses of rain fell, seeming to displace the very atmosphere. But, Oh, the joy we felt! I cried for pure thankfulness, and Robert went to a shaded corner of the piazza, and let the rain pour down upon him.

When the storm was over, there was a new world—a fresh, cool, rejoicing world. It looked as happy as if just made, and the children were eager to get out and play in the little ponds. Robert and I soon rallied. The drop in the temperature was all Robert needed, and I had in those days a wonderful power—not yet quite exhausted—of recuperation. If a trouble was lifted ever so little, I threw it from me; if a sickness took but a right turn, I went surely on to recovery. So as soon as the breathless heat was broken, I began to think of my house and my duties. The children's lessons had been long neglected, and my work basket was full to overflowing with garments to make and to mend.

|

|

4Austin, 1861

Very quickly I was so busy that I had no time for public affairs, and then the war dragged on so long, that my enthusiasm was a little cooled. Also I was troubled somewhat by Robert's continued lack of employment. Food and clothing was dearer, and money scarcer than I had ever before known them, and Robert had become impatient and was entertaining a quite impossible idea—he wanted to rent a farm and get away from the fret and friction of the times. I pointed out the fact that neither of us knew anything about farming, and that Texas farming was special in every department. But in those days it was generally supposed that any man could naturally farm, just as it was expected that every girl naturally knew how to cook and to keep house. At any rate, the idea had taken possession of him, and not even the probability of prowling savages was alarming.

"All that come near the settlements are friendly," he said, "or if not they are too much afraid of the Rangers to misbehave themselves.''

"But, Robert," I answered, "very few of them think killing white women and children 'misbehavior.' "

There is however no use in talking to a Scotchman who has made up his mind. God Almighty alone can change it, so I took to praying. Perhaps it was not very loyal to pray against my husband's plans, but circumstances alter cases, and this farming scheme was a case that had to be altered.

Events which no one had foreseen put a stop to this discussion at least for a time. In the soft, hazy days of a beautiful November, a single word was whispered which sent terror to every heart. It was a new word—the designation of what was then thought to be a new disease, which had been ravaging portions of the Old World, and had finally appeared in the New.

|

|

5Austin, 1861

I had seen it described in Harper's Weekly, and other New York papers, and I was afraid as soon as I heard of it. Robert came home one day and told me Mrs. Carron's eldest daughter was dead, and her other daughter dying. Every hour its victims seemed to increase, and by December all of my friends had lost one or more of their families. I remained closely at home, and kept my children near me. Though they did not know it, I watched them day and night.

On the eighth of December near midnight, I noticed that Ethel had difficulty in nursing and appeared in great distress, and I sent for the doctor with fear and trembling.

"Diphtheria!" he said; and the awful word pierced my ears like a dart, and my spirit quailed and trembled within me. For no cure and no alleviations had then been found for the terrible malady, and indeed many people in Austin contended that the epidemic from which we suffered, was not diphtheria, but the same throat disease which had slain the deer and cattle by thousands during the summer.

In the chill gray dawn of the ninth, as the suffering babe lay apparently unconscious on my knees, the Angel of Death passed by, and gave me the sign I feared but expected—a warning not unkind but inexorable. The next twenty-four hours are indescribable by any words in any language. A little before they ended, the doctor led me into another room. Then I fell on my face at the feet of the Merciful One, and with passionate tears and outcry pleaded for her release—only that the cruel agony might cease—only that—dear, and lovely, and loving as she was, I gave her freely back. I asked now only for her death. I asked Christ to remember his own passion and pity her. I asked all the holy angels who heard me praying to pray with me. If a mortal can take the kingdom of heaven by storm, surely my will to do so at that hour stood for the deed. Breathless, tearless, speechless, I lay at last at His Mercy. And it faileth not! In a few minutes Robert entered. He looked as men look who come out of the Valley of the Shadow of Death. I thought he also was dying. I stood up and looked anxiously into his face, and he drew me to his heart, and said softly, "All is over, Milly. She has gone."

|

Puberty and Adolescence in Girls

by Mary Scharlieb, M.D.

Mary Scharlieb (1845-1930) was a pioneer British female physician in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1888, she became the first British woman to gain the M.D. degree. In 1928, she was made a Dame of the British Empire for her medical and social work.

This excerpt comes from Chapter 1 of her book, Youth and Sex: Dangers and Safeguards for Girls and Boys, published in 1919. Dr. Scharlieb wrote the section dealing with girls, and Mr. Silby wrote the section dealing with boys. So, for this assignment, consider Mary Scharlieb as the author of the article.

NOTE: The article contains several words that have British spellings, such as recognised and colour. Remember to quote accurately if you use these correct variant spellings.

|

Puberty and Adolescence in Girls

by Mary Scharlieb, M.D.

1. Changes in the Bodily Framework.

During this period the girl's skeleton not only grows remarkably in size, but is also the subject of well-marked alterations and development. Among the most evident changes are those which occur in the shape and inclination of the pelvis. During the years of childhood the female pelvis has a general resemblance to that of the male, but with the advent of puberty the vertical portion of the hip bones becomes expanded and altered in shape, it becomes more curved, and its inner surface looks less directly forward and more towards its fellow bone of the other side. The brim of the pelvis, which in the child is more or less heart-shaped, becomes a wide oval, and consequently the pelvic girdle gains considerably in width.

The heads of the thigh bones not only actually, in consequence of growth, but also relatively, in consequence of change of shape in the pelvis, become more widely separated from each other than they are in childhood, and hence the gait and the manner of running alters greatly in the adult woman. At the same time the angle made by the junction of the spinal column with the back of the pelvis, known as the sacro-vertebral angle, becomes better marked, and this also contributes to the development of the characteristic female type.

No doubt the female type of pelvis can be recognised in childhood, and even before birth, but the differences of male and female pelves before puberty are so slight that it requires the eye of an expert to distinguish them. The very remarkable differences that are found between the adult male and the adult female pelvis begin to appear with puberty and develop rapidly, so that no one could mistake the pelvis of a properly developed girl of sixteen or eighteen years of age for that of a boy. These differences are due in part to the action of the muscles and ligaments on the growing bones, in part to the weight of the body from above and the reaction of the ground from beneath, but they are also largely due to the growth and development of the internal organs peculiar to the woman.

|

|

2Puberty and Adolescence in Girls

All these organs exist in the normal infant at birth, but they are relatively insignificant, and it is not until the great developmental changes peculiar to puberty occur that they begin to exercise their influence on the shape of the bones. This is proved by the fact that in those rare cases in which the internal organs of generation are absent, or fail to develop, there is a corresponding failure in the pelvis to alter into the normal adult shape. The muscles of the growing girl partake in the rapid growth and development of her bony framework. Sometimes the muscles outgrow the bones, causing a peculiar lankiness and slackness of figure, and in other girls the growth of the bones appears to be too rapid for the muscles, to which fact a certain class of "growing pain" has been attributed.

Another part of the body that develops rapidly during these momentous years is the bust. The breasts become large, and not only add to the beauty of the girl's person, but also manifestly prepare by increase of their glandular elements for the maternal function of suckling infants.

Of less importance so far as structure is concerned, but of great importance to female loveliness and attractiveness, are the changes that occur in the clearing and brightening of the complexion, the luxuriant growth, glossiness, and improved colour of the hair, and the beauty of the eyes, which during the years which succeed puberty acquire a new and singularly attractive expression.

The young girl's hands and feet do not grow in proportion with her legs and arms, and appear to be more beautifully shaped when contrasted with the more fully developed limb.

|

|

3Puberty and Adolescence in Girls

With regard to the internal organs, the most important are those of the pelvis. The uterus, or womb, destined to form a safe nest for the protection of the child until it is sufficiently developed to maintain an independent existence, increases greatly in all its dimensions and undergoes certain changes in shape; and the ovaries, which are intended to furnish the ovules, or eggs (the female contribution towards future human beings), also develop both in size and in structure.

Owing to rapid growth and to the want of stability of the young girl's tissues, the years immediately succeeding puberty are not only those of rapid physiological change, but they are those during which irreparable damage may be done unless those who have the care of young girls understand what these dangers are, how they are produced, and how they may be averted.

With regard to the bony skeleton, lateral curvature of the spine is, in mild manifestation, very frequent, and is too common even in the higher degrees. The chief causes of this deformity are:

(1) The natural softness and want of stability in the rapidly growing bones and muscles;

(2) The rapid development of the bust, which throws a constantly increasing burden on these weakened muscles and bones; and

(3) The general lassitude noticeable amongst girls at this time which makes them yield to the temptation to stand on one leg, to cross one leg over the other, and to write or read leaning on one elbow and bending over the table, whereas they ought to be sitting upright. Unless constant vigilance is exerted, deformity is pretty sure to occur--a deformity which always has a bad influence over the girl's health and strength, and which, in those cases where it is complicated by the pathological softness of bones found in cases of rickets, may cause serious alteration in shape and interfere with the functions of the pelvis in later life.

|

|

4Puberty and Adolescence in Girls

2. Changes in the Mental Nature.

These are at least as remarkable as the changes in the bodily framework. There is a slight diminution in the power of memorising, but the faculties of attention, of reasoning, and of imagination, develop rapidly. Probably the power of appreciation of the beautiful appears about this time, a faculty which is usually dormant during childhood. More especially is this true with regard to the beauty of landscape; the child seldom enjoys a landscape as such, although isolated beauties, such as that of flowers, may sometimes be appreciated.

As might be anticipated, all things are changing with the child during these momentous years: its outlook on life, its appreciation of other people and of itself, alter greatly and continuously. The wonderfully rapid growth and alterations in structure of the generative organs have their counterpart in the mental and moral spheres; there are new sensations which are scarcely recognised and are certainly not understood by the subject: vague feelings of unrest, ill-comprehended desires, and an intense self-consciousness take the place of the unconscious egoism of childhood.