Most of the reading you will have to do in college will be referential in nature. Most of the writing you will have to do in college will also be referential in nature. Being well acquainted with the referential purpose will help you immensely in your college career.

The focus of the referential purpose is on factual information. In its two main forms, the referential purpose is used to present factual information or to draw logical conclusions based on those facts. Referential writing presents a thesis, then provides evidence that supports the thesis.

Main Forms of Referential Purpose

Referential-Informative Purpose

The referential-informative form presents information that is factual, accurate, objective, and comprehensive. This form simply gives facts and does not interpret them. This form answers the traditional questions Who, What, When, Where, How? An encyclopedia article on a topic would be a good example of referential-informative writing. A newspaper report on a crime would be another good example.

Example:

3 August 1728

On 3 August 1728 two ladies going in a chariot from Beckingham to Bromley, were robbed by a single highwayman. On Saturday evening the Rev. Uvedale's Lady, and another Gentlewoman, coming over the Chace to Enfield in a coach, were robb'd by 3 highwaymen.

(The Weekly Journal)

|

The writer tells who, what, when, where, and how in the news report.

Referential-Interpretive Purpose

The referential-interpretive form presents logical conclusions that are solidly based on the facts given. In this form, the writer gives facts and makes inferences or draws conclusion based on those facts. An investigation analyzing irregular accounting practices at a big company would likely have a referential-interpretive report at the end. Facts about the accounting practices would be given, and a conclusion about the regularity of the practices would be reached.

Two things must happen for interpretive writing to succeed.

- First, the conclusions must be based on the facts given.

- Second, the facts given must support the conclusion.

The analyses you will write later in the semester are examples of referential-interpretive writing. In such analyses, you use the facts of the article or story to draw your conclusions.

|

Example:

Patience Kershaw uses the expressive purpose in "The Testimony of Patience Kershaw." One main characteristic of expressive writing, the use of first-person pronouns, is evident through most of the article. For example, the girl says in the first sentence, "My father has been dead about a year." Kershaw uses a second characteristic of expressive writing, personal experiences, as she testifies about her work in the coal mines. She says, "I go to pit at five o'clock in the morning." She also gives details about the work she must do in the mines and the conditions she must work in.

|

The writer of the analysis makes logical conclusions and supports the conclusions with facts from the article. The first, second, and fourth sentences would be considered analytical conclusions, and the other sentences give supporting facts from the article.

Other Referential Forms

You may encounter other forms of referential writing in your reading, but you will not deal with them in this course. This section is meant to give you a passing knowledge of the forms.

Referential-exploratory writing is more speculative than informative or interpretive. In referential-exploratory writing, the writer presents a thesis in the form of a question:

- How can pollution from automobiles be reduced?

- What would happen if marijuana were legalized in the United States?

Then, alternative explanations or possible solutions are presented. For the first question, the writer might present facts about how automobiles are built or how oil is refined. For the second question, the writer might look to the situation in The Netherlands, where marijuana has been legalized. Facts about use or criminal activity could be presented to suggest what might happen in this country if marijuana were legalized. Be aware that the answer to the question is not factual nor is it necessarily interpretive; it is speculative.

Referential-reflective purpose is the least objective of the referential forms. This kind of writing, made popular with the New Journalism of the 1960s and 1970s, tends to dramatize reality. This form is also known as parajournalism. The writer deals with real people but uses literary techniques to explain a real situation. The writer may use a dramatic structure, telling the story as though it were a narrative plot. First-person narration is often used in this form, and the objectivity of the writing is often compromised by personal opinions. In some regards, this form is more expressive than referential. Jack London's eyewitness report on the 1906 San Francisco earthquake is a good example of this form of the referential purpose.

This form of writing helped Janet Cooke of the Washington Post to win the 1981 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing. When it was discovered that her award-winning article about an 8-year-old heroin addict was fiction, Cooke lost the prize. (In her defense, Cooke said that the title character in the "Jimmy's World" article was a composite character and not just one real person.)

Kinds of Referential Writing

- Factual newspaper or magazine articles

- Scientific or historical articles in journals

- Articles in an encyclopedia or reference book

- Analysis of symbolism in a novel

- Nonfiction books

- Book or movie reviews

Features and Characteristics

- Focus is on factual information.

- Purpose: to inform (referential-informative); to interpret facts (referential-interpretive)

- Style:

- formal/informal (standard grammar and usage; typical in college writing)

- objective language

- use of third-person pronouns

- Main Characteristics:

- thesis that gives overview or main idea of article or essay

- factual evidence: comprehensive, objective, accurate information

- lack of bias or slant in presenting the information

- logical conclusions drawn from facts given (referential-interpretive)

- Minor Characteristics:

- unambiguous language

- no slang

- no first-person and second-person pronouns

- Forms:

- informative

- interpretive

- exploratory

- reflective or parajournalistic

When You Use the Referential Purpose to Write

- Write a thesis statement that presents an overview or the main idea of your information. The thesis statement is underlined in the example below.

- Present accurate and comprehensive evidence to support your thesis.

- To be comprehensive, your information should answer the questions who, what, when, where, how. To be interpretive, your conclusion should answer the question why.

- Do not speculate or give personal opinions.

- Be objective and unbiased.

- Do not use first-person or second-person pronouns.

- Use formal or informal language, not slang or colloquial language.

|

Example (referential-informative):

The Battle of the Alamo took place in San Antonio, Texas, during the early part of 1836. A group of about 180 men, led by William Travis, David Crockett, and James Bowie, fortified an old Spanish mission known as the Alamo. The small group of men was able to thwart the advance of Mexican troops led by General Santa Anna for a period of 13 days. Finally, on March 6, 1836, the Alamo fell to the superior Mexican force, its defenders dead.

|

When You Analyze the Referential Purpose in Another's Writing

- Identify the purpose you are analyzing, in this case referential-informative writing.

- Directly identify the characteristics (at least three) of the referential-informative purpose used by the writer, such as a thesis, comprehensive facts to support the thesis, accurate and unbiased presentation of information, appropriate style.

- Give an example of each characteristic you identify. Tie the example directly to the characteristic.

- Provide a summative conclusion that the presence of the characteristics demonstrates the use of the purpose.

Example of analysis of the paragraph above:

(The following paragraph is an example of referential-interpretive writing, or critical analysis.)

The writer uses the referential-informative purpose to give information about the Battle of the Alamo. The writer uses one characteristic of referential writing, a thesis, by providing an overview in the first sentence of the paragraph. The writer then uses another characteristic of referential writing, comprehensive presentation of facts, to tell the who, what, when, where, and how of the battle. For example, he notes that "on March 6, 1836, the Alamo fell to the superior Mexican force," giving several facts about the fight. The writer also uses unbiased, informal language, another characteristic of the purpose, to present the facts, as in the example above. The presence of these various characteristics demonstrates the writer's effective use of the referential purpose.

Notes on this analysis:

First sentence: identifies the purpose.

Second sentence: identifies a characteristic of referential writing and includes a related example.

Third and fourth sentences: identifies another characteristic of referential writing and includes a related example.

Fifth sentence: identifies a third characteristic of referential writing and refers to an earlier example.

Sixth sentence: gives a summative conclusion and concise evaluation.

Back to top

MORE REFERENTIAL EXAMPLES

Primary Purpose: Referential-Informative

Main Patterns: Narration, Description

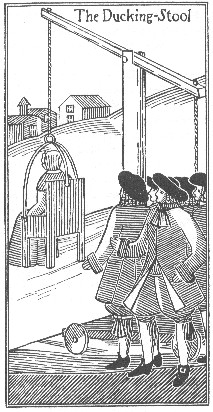

Ducking Stools

In the 17th century, it was illegal for women to be scolds. A scold is someone who is noisy or quarrelsome. Women who were scolds were often punished publicly. The typical punishment was to plunge the scold repeatedly into the water using a ducking stool. There were many designs for such ducking machines. The excerpt below gives details about one kind of ducking stool. The excerpt is from page 14 in Curious Punishments of Bygone Days, by Alice Morse Earle, published by Herbert S. Stone & Co., Chicago, 1896.

|

Ducking Stool

The trebuchet, or trebucket, was a stationary and simple form of a ducking machine consisting of a short post set at the water's edge with a long beam resting on it like a see-saw. By a simple contrivance it could be swung round parallel to the bank, and the culprit tied in the chair affixed to one end. Then the offender could be swung out over the water and see-sawed up and down into the water.

The trebuchet, or trebucket, was a stationary and simple form of a ducking machine consisting of a short post set at the water's edge with a long beam resting on it like a see-saw. By a simple contrivance it could be swung round parallel to the bank, and the culprit tied in the chair affixed to one end. Then the offender could be swung out over the water and see-sawed up and down into the water.

When this machine was not in use, it was secured to a stump or bolt in the ground by a padlock because when left free it proved too tempting and convenient an opportunity for tormenting village children to duck each other.

|

Primary Purpose: Referential-Informative

Main Patterns: Description, Classification

Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China stretches from the western city of Jiayuguan to the Yellow Sea. Between these points, the wall zigzags across 2,150 miles of differing terrain. It is so long and massive that astronauts can see the wall as they orbit Earth. Building the wall took 1,800 years and millions of laborers.

Around 200 B.C., the Chinese emperor Shi Huangdi decided to build the wall to keep Mongolian invaders out of China. The wall followed the rise and fall of the land. It ran along rivers instead of across them and up hills rather than around them. By the end of Shi Huangdi's 15-year rule, about 1,200 miles of the Great Wall had been constructed.

The excerpt is from An Historical, Geographical, and Philosophical View of the Chinese Empire, pages 273-275, by William Winterbotham. The book was printed for and sold by the editor, J. Ridgway, York Street; and W. Button, 1795. The photograph is from the National Archives and Records Administration: "Troop L, 6th U.S. Cavalry, at the Great Wall of China, East of Nan-Kow Pass, 1900."

|

Great Wall of China

The pyramids of Egypt are little, when compared with a wall which covers three large provinces, stretches along an extent of fifteen hundred miles, and is of such an enormous thickness, that six horsemen may easily ride abreast upon it. . . . One third of the able bodied men of China were employed in constructing this wall, and the workmen were ordered, under pain of death, to place the materials of which it was composed so closely that the least entrance might not be left for any instrument of iron. . . .

The foundation consists of large blocks of square stones laid in mortar; but all the rest is constructed of bricks. The whole is so strong, and well built, that it scarcely needs any repairs. . . . When carried over steep rocks where no horse can pass, it is about fifteen or twenty feet high, and broad in proportion; but when running through a valley, or crossing a river, you behold a strong wall, about thirty feet high, with square towers at certain intervals. . . . The top of the wall is flat, and paved with cut stone; and where it rises over a rock or eminence, there is an ascent by easy stone stairs.

|

Primary Purpose: Referential-Interpretive

Main Patterns: Narration, Description (Analysis)

Analysis of Conflict in a Short Story

The paragraph below is an example of referential-interpretive analysis of an element in a fictional short story. The paragraph discusses the central character's main conflict in Maupassant's "The Necklace." The writer draws analytical conclusions based on facts of the story. You might write this kind of paragraph in English 1302.

|

Mathilde's central internal conflict of self-deceit vs. reality, or fantasy vs. reality, is apparent from the beginning. Mathilde cannot tell the real from the false in her life. When her husband gains the invitation, she claims she has nothing to wear. Her frugal husband, a foil who represents her reality, suggests that she wear her theater dress and flowers. Mathilde tells her husband to give the invitation to some man "'whose wife is better equipped'" than she is, pointing out her need of material things to substantiate her errant self-image. A new dress easily solves one minor conflict, but she is unsatisfied. She needs jewels to complete the illusion because, as she says, "'there's nothing more humiliating that to look poor among other women who are rich.'" She decides to borrow jewelry from her rich friend, Mme. Forestier, a foil who represents Mathilde's illusion. The diamond necklace she borrows completes her illusion, and a Cinderella is born. She is a hit at the ball, which she credits to the necklace. As she leaves in a rush so as not to be detected in a modest cloak "whose poverty contrasted with the elegance of the ball dress," she loses the borrowed necklace. Indeed, this contrast of apparel highlights Mathilde's internal conflict, fantasy vs. reality.

|

Primary Purpose: Referential-Interpretive

Main Patterns: Classification, Evaluation

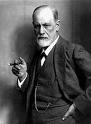

The Interpretation of Dreams

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) was a groundbreaking psychoanalyst in the late 1800s. His theories of ego and sexuality were controversial in his times. The excerpt is from Chapter 1, page 7 in The Interpretation of Dreams by Sigmund Freud, originally published in 1899. The excerpt was translated by A.A. Brill, 1911.

|

The Interpretation of Dreams

As has been said, those writers of antiquity who preceded Aristotle did not regard the dream as a product of the dreaming psyche, but as an inspiration of divine origin, and in ancient times, the two opposing tendencies which we shall find throughout the ages in respect of the evaluation of the dream-life, were already perceptible. The ancients distinguished between the true and valuable dreams which were sent to the dreamer as warnings, or to foretell future events, and the vain, fraudulent and empty dreams, whose object was to misguide him or lead him to destruction.

As has been said, those writers of antiquity who preceded Aristotle did not regard the dream as a product of the dreaming psyche, but as an inspiration of divine origin, and in ancient times, the two opposing tendencies which we shall find throughout the ages in respect of the evaluation of the dream-life, were already perceptible. The ancients distinguished between the true and valuable dreams which were sent to the dreamer as warnings, or to foretell future events, and the vain, fraudulent and empty dreams, whose object was to misguide him or lead him to destruction.

|

Primary Purpose: Referential-Interpretive

Main Patterns: Narration, Description, Evaluation

The Discovery of the Universe

Joseph McCabe (1856-1939) was one of the main figures in English atheism and the Freethinker movement. He was also a prolific author on controversial topics. The excerpt below is from Chapter 1 of The Story of Evolution, by Joseph McCabe, published in 1912.

|

The Discovery of the Universe

The beginning of the victorious career of modern science was very largely due to the making of two stimulating discoveries at the close of the Middle Ages. One was the discovery of the earth: the other the discovery of the universe. Men were confined, like molluscs in their shells, by a belief that they occupied the centre of a comparatively small disk--some ventured to say a globe--which was poised in a mysterious way in the middle of a small system of heavenly bodies. The general feeling was that these heavenly bodies were lamps hung on a not too remote ceiling for the purpose of lighting their ways.

The beginning of the victorious career of modern science was very largely due to the making of two stimulating discoveries at the close of the Middle Ages. One was the discovery of the earth: the other the discovery of the universe. Men were confined, like molluscs in their shells, by a belief that they occupied the centre of a comparatively small disk--some ventured to say a globe--which was poised in a mysterious way in the middle of a small system of heavenly bodies. The general feeling was that these heavenly bodies were lamps hung on a not too remote ceiling for the purpose of lighting their ways.

Then certain enterprising sailors--Vasco da Gama, Maghalaes, Columbus--brought home the news that the known world was only one side of an enormous globe, and that there were vast lands and great peoples thousands of miles across the ocean. The minds of men in Europe had hardly strained their shells sufficiently to embrace this larger earth when the second discovery was reported. The roof of the world, with its useful little system of heavenly bodies, began to crack and disclose a profound and mysterious universe surrounding them on every side. One cannot understand the solidity of the modern doctrine of the formation of the heavens and the earth until one appreciates this revolution.

|

|

2The Discovery of the Universe

Before the law of gravitation had been discovered it was almost impossible to regard the universe as other than a small and compact system. We shall see that a few daring minds pierced the veil, and peered out wonderingly into the real universe beyond, but for the great mass of men it was quite impossible. To them the modern idea of a universe consisting of hundreds of millions of bodies, each weighing billions of tons, strewn over billions of miles of space, would have seemed the dream of a child or a savage. Material bodies were "heavy," and would "fall down" if they were not supported. The universe, they said, was a sensible scientific structure; things were supported in their respective places. A great dome, of some unknown but compact material, spanned the earth, and sustained the heavenly bodies. It might rest on the distant mountains, or be borne on the shoulders of an Atlas; or the whole cosmic scheme might be laid on the back of a gigantic elephant, and--if you pressed--the elephant might stand on the hard shell of a tortoise. But you were not encouraged to press.

The idea of the vault had come from Babylon, the first home of science. No furnaces thickened that clear atmosphere, and the heavy-robed priests at the summit of each of the seven-staged temples were astronomers. Night by night for thousands of years they watched the stars and planets tracing their undeviating paths across the sky. To explain their movements the priest-astronomers invented the solid firmament. Beyond the known land, encircling it, was the sea, and beyond the sea was a range of high mountains, forming another girdle round the earth. On these mountains the dome of the heavens rested, much as the dome of St. Paul's rests on its lofty masonry. The sun travelled across its under-surface by day, and went back to the east during the night through a tunnel in the lower portion of the vault. To the common folk the priests explained that this framework of the world was the body of an ancient and disreputable goddess. The god of light had slit her in two, "as you do a dried fish," they said, and made the plain of the earth with one half and the blue arch of the heavens with the other.

|

Back to Primer Contents

© Site maintained by D. W. Skrabanek

English/Austin Community College

Last update: October 2012