"When All the Experts Got It Wrong:

Harry Truman's Upset Presidential Victory,

1948

L. Patrick Hughes, Austin Community College

With mischievous glee, President Truman hoisted the

post-election copy of the Chicago Daily Tribune aloft for all in

the assembled crowd at Union Station to see. One lucky journalist caught

the moment on film, producing one of the most memorable political photographs

of the twentieth century.

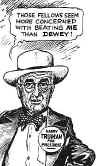

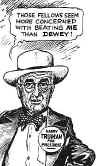

So utterly convinced was the partisan Republican

paper from the nation's heartland that challenger Thomas E. Dewey would

defeat the embattled incumbent, its editors had rushed the issue with the

screaming headline "Dewey Defeats Truman" to newsstands prior to the close

of voting. While it backfired, the decision had appeared reasonable. Every

public opinion poll conducted throughout 1948 had shown Truman losing.

The outcome appeared so certain, the respected Gallup organization had

quit collecting data ten days before the election. Defections and insurgencies

within the president's own party seemingly doomed his chances. Progressive

party candidate Henry A. Wallace appealed to disgruntled northern liberals

while irate southern segregationists vowed to cast their ballots for Strom

Thurmond and the States Rights/"Dixiecrat" party. Republicans, confident

of their return to the Oval Office for the first time in sixteen years,

were already celebrating victory. Only Truman felt he had a chance. It

thus came as an absolute shock when the fiery Missouri banty rooster triumphed

with the voters and all the experts were left to explain how they had gotten

it so completely wrong.

The Death of the New Deal Spirit and the Republican

Resurgence

President Truman's reelection in 1948 was so startling

to many because it seemed to run against the tide of an increasingly conservative

political trend in the United States. World War II, in many ways, marked

the death of the New Deal spirit of reform which had characterized the

depression years of the 1930s. Having been called upon to make personal

sacrifices on numerous fronts in order to defeat the threat of the Axis

powers, Americans emerged from the war hoping to make up for lost ground.

They looked forward to an immediate return of economic prosperity. People

were tired of governmental controls such as wage and price restrictions,

rationing, etc. and demanded their rapid abandonment by the Truman administration.

Instead, shortages of food, fuel, and other commodities seemed to continue

unnecessarily. When peace didn't produce instant prosperity and unfettered

opportunity, citizens blamed Truman, who presided over their nation only

because of Franklin Roosevelt's death in April 1945. Millions of citizens

knew absolutely nothing about the man from Missouri who spoke with the

funny Midwest twang and wore glasses with lenses that looked like the bottoms

of coke bottles. More and more questioned the country's direction under

his leadership.

The Republican party, hoping to take advantage of

the building dissatisfaction with the status quo, launched its quest to

take back Congress in 1946 utilizing slogans such as "Had Enough?" and

"It's Time for a Change." The most partisan sported campaign buttons proclaiming

"To Err is Truman." If victorious, Republican National Committee Chairman

B. Carroll Reece promised an end to controls and the return of "orderly,

capable and honest government." The strategy struck a chord with voters.

Republican candidates swept to victory in most parts of the country. Picking

up fifty-six seats in the House of Representatives and thirteen seats in

the Senate, Republicans gained control of Congress, began steering the

country in a more conservative direction domestically, and set their sights

on recapturing the presidency two years hence.

While the new Republican 80th Congress

supported the president in foreign affairs, approving the Truman Doctrine,

the Marshall Plan, and aid for Greece and Turkey as the Cold War with the

Soviet Union began in earnest, confrontation and conflict beset the domestic

arena. President Truman, hoping to moderately further the New Deal revolution

of his predecessor, proposed extensions of and increased funding for education,

housing, subsidized medical care for the elderly, and social security.

His proposals came to naught on Capitol Hill, where conservatives of both

parties by and large ignored these "Fair Deal" initiatives. Instead, Congress

passed the Taft-Hartley Act over presidential veto in 1947. Fearing that

labor unions had grown too powerful and were in the hands of left-leaning

extremists, congressmen attacked one of the Democratic Party's most important

constituencies - organized labor. The legislation outlawed the "closed

shop," where union membership was a prerequisite to employment, and banned

secondary boycotts. Congress and president clashed over budget appropriations.

Truman three times vetoed what he saw as a dangerous tax reduction bill

before it became law over his opposition. Additionally, presidential spending

proposals were consistently reduced before enactment. The momentum of reform,

which had swept across America in the preceding decade, appeared stymied

at every turn and the president's approval rating spiraled downward.

A Party in Turmoil

Equally frustrating to Truman had to be the growing

factionalism within his own ranks. While the "Roosevelt Coalition," fashioned

in the mid-Thirties, returned Democrats to dominance for the first time

in three-quarters of a century, the union of so many divergent and oft-conflicting

elements was difficult to manage at best. More often than not, Democrats

spent more time fighting one another than doing battle against their Republican

opponents. Numerous issues drove a wedge between the wings of the party.

As the approaching 1948 presidential election lay

just over the horizon, ideological tensions rent the Democratic Party into

three factions, each of which could play a pivotal part in determining

the outcome of the upcoming contest.

The most liberal elements of the coalition believed

Truman far too conservative; he was too willing to compromise with reactionary

elements and had abandoned the liberal principles of his predecessor. He

had led the party to its sweeping defeat in 1946 and appeared incapable

of driving his Fair Deal initiatives through the Republican Congress. Civil

rights progress was of critical importance to such individuals from both

ideological and pragmatic political perspectives. Ending the American system

of "separate but equal" segregation and political disfranchisement was

a moral imperative for them. How could the United States do battle with

the Soviet Union for the future of the world if our own system of apartheid

went unchallenged? From a more immediate and pragmatic point of view, cementing

the newly won Black constituency was necessary for political survival.

The massive migration of Blacks from the Deep South to northern industrial

centers during the Great Depression and World War II changed the political

landscape entirely. Here was a growing constituency no longer disfranchised

as it had been in Dixie. Able to fully exercise their constitutional rights

at the ballot box, Black citizens no longer suffered in silence. Moral

considerations notwithstanding, ignoring such a potentially powerful constituency

amounted to political suicide.

At the other extreme lay the southern wing of the

party. Committed to smaller, less active government, southern Democrats

had historically resisted federal activism and intrusion into what were

seen as purely local matters south of the Mason-Dixon line. Support of

Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal agenda at the depths of the Great Depression

occurred only when it was the only alternative to either Herbert Hoover

or revolution in the streets. This, however, was an anomaly. Once economic

conditions stabilized by 1937, conservatives from Dixie abandoned the president

and party liberals, opposing court packing, executive branch reorganization,

wages & hours legislation, pro-labor proposals, and compensatory federal

spending. Entering into a congressional coalition with Republicans, they

halted the New Deal in its tracks. Because of their long heritage, they

were as yet unwilling to become Republicans. That possibility, however,

was not out of the question should their liberal brethren push civil rights

change down their throats.

Historically essential to the party's success in

national elections, the southern wing was adamantly opposed to ANY

federal action in the field of race relations. Since the final withdrawal

of federal troops from their region ending the Reconstruction era in 1877,

southerners, Democrats all, had demanded "home rule" as the price of their

support. It was their litmus test and they held what amounted to veto power

over the election of Democratic presidential candidates. Should they abandon

the nominee, the northern wing by itself lacked the votes in the Electoral

College to successfully challenge the Grand Old Party. Similarly, the region's

representatives in Congress enjoyed, indeed flaunted, a stranglehold over

actions in Washington, D. C. Manipulation of the seniority system gave

southerners powerful committee chairmanships, made them invaluable to Democratic

presidents, and allowed them to squelch demands for action in the field

of civil rights. Even Franklin Roosevelt refused to go to the mat on this

topic; he simply couldn't afford to lose the support of such congressional

titans in dealing with the economic catastrophe of the depression in the

Thirties. If all else failed, southern senators could always fall back

on the filibuster technique to kill civil rights proposals; no such filibuster

had ever been broken by the invocation of cloture.

Ideological moderates and pragmatists occupied the

middle ground. Aware of the increasing insistence of northern liberals

for civil rights progress regardless of political consequences and the

determination of southern conservatives to block such change even if it

plunged the party into electoral oblivion, moderates and pragmatists held

the fate of civil rights and the Democratic party in their hands. Could

fratricidal intra-party warfare over the issue somehow be avoided? Was

the moral issue worth the loss of national office and the control of Congress?

Would they allow pragmatism to forever override the moral imperative of

racial justice and equality under the law?

The Cauldron Boils Over

This long-festering quandary boiled over in early

1948 when President Truman, who had never evidenced any commitment to racial

equality, bit the bullet, becoming the first chief executive since Reconstruction

to demand legislation in the field of civil rights. The president had appointed

a blue ribbon commission in 1946 to examine the state of race relations

in the United States. The panel made public its report, entitled "To Secure

These Rights," in 1947. The document shocked Truman, aghast at the horrors

of discrimination and bigotry he found detailed therein. The commission's

proposals - a permanent Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC), creation

of a permanent civil rights commission, and the denial of federal monies

to segregated schools - became the basis for Truman's call to arms on February

2, 1948. Even before his civil rights message to Congress, southern Democrats

were reacting to the commission's report. Said newly-elected Governor Fielding

Wright of Mississippi in his January inaugural address: "As a lifelong

Democrat, as a descendant of Democrats, as governor of the most Democratic

state, I would regret to see the day come when Mississippi or the South

should break with the Democratic party in a national election. But vital

principles and eternal truths transcend party lines. We must make our leaders

fully realize we mean precisely what we say and we must, if necessary,

implement our words with positive action. We warn them now to take heed."

Truman, facing reelection and needing the votes of

both southern conservatives and northern liberals including Blacks, went

forward despite the ominous warnings emanating from Dixie. The president

called upon Congress to abolish the poll tax, enact a federal anti-lynching

law, create the FEPC, establish a permanent commission on civil rights,

and ban segregation in all interstate transportation vehicles and facilities.

The explosion from southerners was instantaneous.

Senator James O. Eastland (D-Mississippi) stated "this proves that organized

mongrel minorities control the government" while Representative Gene Cox

(D-Georgia) expounded that Truman's proposals "sound like the program of

the Communist Party." Governor Strom Thurmond (D-Georgia) termed the president's

initiative "a stab in the back" that would be "as detrimental to the South

as those proposed in the Reconstruction period by the Republican party."

Southern governors, preparing to meet in Florida to plot strategy on how

to kill the measures, warned Democratic Party chairman Howard McGrath that

"the South is no longer in the bag." Indeed, Governor Thurmond called for

southerners to "stand together in the Electoral College" in the upcoming

national election. His strategy, if successful, would deny either party

a majority and the election's outcome would be thrown into the House of

Representatives where the South could demand the defeat of the Truman bills

for its support.

Faced with the possible defection of the southern

wing, the president did little to push congressional enactment of his civil

rights proposals. That could wait until after the election. He therefore

attempted to downplay the issue in order to avoid further alienating Dixie.

Rebellion was unavoidable at the other end of the

ideological spectrum. Ultraliberals, for the moment at least, stood mesmerized

by the siren's song of Henry A. Wallace, ex-Secretary of Agriculture, ex-Secretary

of Commerce, and Franklin Roosevelt's second vice-president. Unacceptable

as chief executive to party leaders aware FDR was unlikely to survive a

fourth term of office, Wallace had been jettisoned from the national ticket

in 1944 in favor of the more moderate Senator Truman. Four years later,

those of the Democratic extreme-left set out to rectify the injustice which

had denied their champion the presidency upon Roosevelt's death in April

1945. Rejecting what they saw as Truman's more conservative domestic policies

and bewailing the dissolution of the country's wartime alliance with the

Soviet Union, Wallace supporters embarked upon a quixotic crusade to oust

the interloper from Missouri. They were little concerned about the electability

of their own hero as a third party candidate. At minimum, a challenge from

the far left might force the incumbent in a more liberal direction at home

and to adopt a more conciliatory attitude abroad.

As the president and his closest advisors formulated

strategy for the upcoming campaign, Truman understood instinctively that

above all else he must occupy the middle ground. With Wallacites already

in revolt and Dixie teetering on the brink, the Missouri pragmatist realized

any attempt to placate extremists was likely to be counterproductive. The

"red hots" were loud in volume but few in number. The great mass of voters

in both his own party and the general electorate lay in the middle, the

broad political mainstream. Far better to adhere to his present course,

portray his tormentors as radicals likely to plunge party and nation into

turmoil, and appeal to moderates of all persuasions.

The embattled president had additional reason to

look past the doom and gloom of the current situation. A seasoned political

veteran, he was aware that many of his critics of spring and summer would

probably return to the fold on Election Day, especially if he gave them

reason to do so. Throughout the republic's history, early rhetorical support

for third- and fourth-party insurgents inexorably evaporates in the harsh

light of November reality. Third parties never win, or so

the overwhelming majority of Americans believe. Therefore, a ballot cast

for a minor party candidate may give vent to the spleen but forfeits any

impact on the outcome of the real contest between major party nominees.

Even when less than satisfied with the major contenders, most citizens

swallow hard and vote for the one considered less objectionable. Such an

oft-repeated phenomenon was likely to reoccur yet again in 1948. The key

for Truman was in persuading the majority of the temporarily dissatisfied

that he was the least objectionable of the viable alternatives. Some events,

however, were beyond his control as delegates to the Democratic nominating

convention began assembling in Philadelphia.

The embattled president had additional reason to

look past the doom and gloom of the current situation. A seasoned political

veteran, he was aware that many of his critics of spring and summer would

probably return to the fold on Election Day, especially if he gave them

reason to do so. Throughout the republic's history, early rhetorical support

for third- and fourth-party insurgents inexorably evaporates in the harsh

light of November reality. Third parties never win, or so

the overwhelming majority of Americans believe. Therefore, a ballot cast

for a minor party candidate may give vent to the spleen but forfeits any

impact on the outcome of the real contest between major party nominees.

Even when less than satisfied with the major contenders, most citizens

swallow hard and vote for the one considered less objectionable. Such an

oft-repeated phenomenon was likely to reoccur yet again in 1948. The key

for Truman was in persuading the majority of the temporarily dissatisfied

that he was the least objectionable of the viable alternatives. Some events,

however, were beyond his control as delegates to the Democratic nominating

convention began assembling in Philadelphia.

"Philadelphia Freedom"

As the quadrennial convocation of Democrats began

in the "City of Brotherly Love," love, brotherly or otherwise, was nowhere

to be found. Delegates were in a quarrelsome mood and less than optimistic

about the party's chances in the general election ahead.

Southern firebrands vowed vengeance on Truman. Hoping

against hope to somehow deny him renomination, they warned loudly and repeatedly

that a party embrace of the president's civil rights proposals would result

in a southern walkout and Dixie's defection in November. Liberals such

as Hubert Humphrey, reformist mayor of Minneapolis and candidate for the

United States Senate, were of the opposite mind. Driven equally by conviction

and political reality in their region of the country, they argued for a

rigorous endorsement of Truman's call for civil rights action. Incumbents

from all geographic sections and ideological factions sought to determine

what course of action would best guarantee their continuation in office.

Now narrowly focused on his reelection bid, President

Truman and his operatives sought party unity and were willing to straddle

the fence in hopes of avoiding a southern walkout. To this end, the administration

exerted its influence on the platform committee to adopt the same mild

plan on civil rights used in previous years to paper over Democratic differences

on the volatile issue. While the position statement maintained Democrats'

belief that minorities had "the right to live, develop, and vote equally

with all citizens," it committed the party to no specific measures to make

that theoretical right reality. The attempted compromise would go to the

convention floor as the majority report of the platform committee but was

unacceptable to northern liberals and southern segregationists, both of

whom vowed to take their opposition to the delegates at large.

Opposition to Truman also took the form of the chimerical

candidacy of Senator Richard Russell. The dean and most influential member

of the southern congressional delegation, Russell, a party loyalist, was

every bit as irate over the prospect of civil rights legislation as firebrands

such as Strom Thurmond and Fielding Wright. He, however, rejected the prospect

of a doomed third party challenge, choosing instead to offer his candidacy

as a rallying point for southern Democrats. The results of the balloting

were not surprising. Delegates selected Truman as their standard bearer

over Russell by a four-to-one margin and named Senator Alben Barkley of

Kentucky as his running mate.

The overwhelming majority of delegates nonetheless

exhibited little hope the incumbent president could somehow lead the party

to victory in November's general election. Truman thought otherwise. In

accepting their nomination, his first words to the delegates reflected

the fighting spirit that would characterize his entire campaign. "Senator

Barkley and I will win this election and make these Republicans like it

- don't you forget that!" His speech excoriated the Republican Party as

the handmaiden of "special interests" and "the privileged few." He then

turned his wrath on what he labeled "the Do-Nothing 80th Congress,"

which had betrayed the people with its mulish inaction over the preceding

year and a half. After listing what he felt were that session's numerous

deficiencies, he electrified the Philadelphia convention by announcing

that he was calling Congress back into special session

"to pass the laws to halt rising prices, to meet

the housing crisis -which they are saying they are for in their platform.

At the same time, I shall ask them to act upon other vitally needed measures,

such as aid to education, which they say they are for; a national health

program; civil rights legislation, which they say they are for; an increase

in the minimum wage, which I doubt very much they are for; extension of

the Social Security coverage and increased benefits, which they say they

are for; funds for projects needed in our program to provide public power

and cheap electricity." "Now my friends, if there is any reality behind

that Republican platform, we ought to get some action from a short session

of the Eightieth Congress. They can do this job in fifteen days, if they

want to do it."

Truman knew of course that a special session would produce

no settlement of the legislative stalemate. The failure of the Republican

congress to enact such programs, however, would highlight Truman's allegation

that it was do-nothing and reactionary Republicans blocking progress. His

call to arms reached out to the New Deal constituencies upon which his

reelection bid would rest and energized Democratic activists across the

nation.

What platform Truman would run on was still to be

determined. True to their word, conservatives from Dixie offered three

different amendments, all of which decried the president's actions and

defended the power of states to maintain segregation. Two were rejected

by voice vote and that offered by former Texas governor Dan Moody fell

by a three-to-one margin. Thurmond lashed out in defeat. "We have been

betrayed and the guilty should not go unpunished." Southerners had to "stand

together, fight together, and if necessary go down together…..We should

place principle above party even if it means political defeat."

In reality, segregationists had never had a chance

on the platform question given their relative lack of numbers. Liberals

from the northeast and Far West were another matter entirely. In a delicious

twist of irony, they determined to challenge the president's wishes on

the platform in order to further his February 2nd call for civil

rights legislation. While Truman was intent on winning the upcoming election,

the moderate left would settle for nothing less than unequivocally committing

the party to the causes of racial equality and justice. The substitute

motion made this clear:

We highly commend President Harry S. Truman for

his courageous stand on the issue of civil rights.

We call upon Congress to support our President in

guaranteeing these basic and fundamental American Principles: (1) the right

of full and equal political participation; (2) the right to equal opportunity

of employment; (3) the right of security of person; (4) and the right of

equal treatment in the service and defense of our nation.

Their gamble hinged on somehow convincing moderate delegates.

That job fell to Hubert Humphrey. As the ebullient Humphrey strode to the

dais to make the case, one Tennessee delegate, sensing what lay ahead,

noted to a reporter that "…you are witnessing here today the dissolution

of the Democratic Party in the South."

Rarely, if ever, has one speaker so completely captivated

a national nominating convention. Decades later, those in attendance could

recall every particular. (See appendix for complete text of Humphrey's

speech.) As Humphrey began his remarks in favor of the minority report,

delegates realized the future of the party and perhaps the nation hung

in the balance. Said the mayor:

Friends, delegates, I do not believe that there

can be any compromise of the guarantees of civil rights which we have mentioned

in the minority report. In spite of my desire for unanimous agreement on

the entire platform, in spite of my desire to see everybody here in unanimous

agreement, there are some matters which I think must be stated clearly

and without qualification. There can be no hedging - no watering down.

The newspaper headlines are wrong.

Friends, delegates, I do not believe that there

can be any compromise of the guarantees of civil rights which we have mentioned

in the minority report. In spite of my desire for unanimous agreement on

the entire platform, in spite of my desire to see everybody here in unanimous

agreement, there are some matters which I think must be stated clearly

and without qualification. There can be no hedging - no watering down.

The newspaper headlines are wrong.

There will be no hedging, and there will be no watering

down, if you please, of the instruments and the principles of the civil

rights program.

My friends, to those who say that we are rushing

this issue of civil rights, I say we are 172 years too late!

Despite every indication that southern delegates were

prepared to walk out of in protest, delegates approved the Humphrey substitute

plan by a vote of 651.5 to 582.5. Between Truman's first ballot nomination

over Richard Russell and passage of the strong civil rights plank, the

South and the new Democratic Party had reached a turning point. To a man,

the Mississippi delegation walked out of the hall in protest. Thirteen

members of the Alabama delegation followed. As later events would demonstrate,

the days of the solid Democratic south were passing into history.

Against All Odds

Immediately following adjournment of the Philadelphia

convention, Governor Fielding of Mississippi and Frank Dixon, former governor

of Alabama, announced plans for a meeting of dissident southerners to convene

in Birmingham. They next approached Governor Thurmond with the idea of

running as a third party candidate. Only thereby could Truman be denied

the south. The South Carolina governor thought the matter over for less

than an hour before agreeing to make the campaign. Delegates quickly nominated

Thurmond and chose Governor Fielding as his running mate. The States' Rights

Party, more popularly known as the Dixiecrats, urged Democratic state officials

throughout the south to substitute Thurmond and Wright for Truman and Barkley

as the Democratic candidates on their official ballots. Their platform,

adopted in record time, decried Truman's civil rights proposals as an invasion

of states rights and alleged they were meant "to embarrass and humiliate

the South." The party envisioned no compromise on the question. "We stand

for the segregation of the races and the racial integrity of each race."

The demand for strict observance of Article X of the Bill of Rights, reserving

to the states all powers not specifically delegated to the federal government

by the Constitution, was stated forcefully. Unless this was done, the rebels

warned, the growth of federal power would soon produce a totalitarian police

state.

Immediately following adjournment of the Philadelphia

convention, Governor Fielding of Mississippi and Frank Dixon, former governor

of Alabama, announced plans for a meeting of dissident southerners to convene

in Birmingham. They next approached Governor Thurmond with the idea of

running as a third party candidate. Only thereby could Truman be denied

the south. The South Carolina governor thought the matter over for less

than an hour before agreeing to make the campaign. Delegates quickly nominated

Thurmond and chose Governor Fielding as his running mate. The States' Rights

Party, more popularly known as the Dixiecrats, urged Democratic state officials

throughout the south to substitute Thurmond and Wright for Truman and Barkley

as the Democratic candidates on their official ballots. Their platform,

adopted in record time, decried Truman's civil rights proposals as an invasion

of states rights and alleged they were meant "to embarrass and humiliate

the South." The party envisioned no compromise on the question. "We stand

for the segregation of the races and the racial integrity of each race."

The demand for strict observance of Article X of the Bill of Rights, reserving

to the states all powers not specifically delegated to the federal government

by the Constitution, was stated forcefully. Unless this was done, the rebels

warned, the growth of federal power would soon produce a totalitarian police

state.

While the insurrection afoot in Dixie was of concern

to the Truman forces, the president and his advisors took note of the fact

that the overwhelming majority of southern Democratic office holders and

party functionaries - some of the most bitter critics of the administration's

civil rights stand - had shunned the call to Birmingham and revolt. They,

it appeared, were concerned above all else with retaining office and their

position within the party. They would repeatedly voice their opposition

to the president's civil rights plan but refused any association with an

undertaking that was clearly electoral folly. Truman would do nothing on

campaign swings through the region to rock the boat. Thus, political pragmatism

doomed the Dixiecrats from the beginning. In only four states, Alabama,

Mississippi, South Carolina, and Louisiana, would Thurmond and Wright appear

on the November ballot in place of Truman and Barkley.

While the insurrection afoot in Dixie was of concern

to the Truman forces, the president and his advisors took note of the fact

that the overwhelming majority of southern Democratic office holders and

party functionaries - some of the most bitter critics of the administration's

civil rights stand - had shunned the call to Birmingham and revolt. They,

it appeared, were concerned above all else with retaining office and their

position within the party. They would repeatedly voice their opposition

to the president's civil rights plan but refused any association with an

undertaking that was clearly electoral folly. Truman would do nothing on

campaign swings through the region to rock the boat. Thus, political pragmatism

doomed the Dixiecrats from the beginning. In only four states, Alabama,

Mississippi, South Carolina, and Louisiana, would Thurmond and Wright appear

on the November ballot in place of Truman and Barkley.

With each passing day it also became more evident

that Henry Wallace and his Progressive Party wouldn't attract the number

of liberal voters necessary to determine the election outcome. Ignoring

the reality of American politics that dooms those perceived as extremists,

the Progressives took positions that drove the majority of liberals running

back to the president. The party platform denounced Truman's "get tough"

policy with the Soviet Union, blaming him for the onset of the Cold War.

Other planks demanded American military disarmament, the abandonment of

West Berlin to the socialist world, the nationalization of all key industries

in the United States, as well as the retirement giveaway known as the Townsend

Plan. While movement leaders denied any communist influence within their

ranks, Wallace refused to repudiate the Communist Party, U.S.A. when it

officially endorsed his candidacy.

That left the Republicans. Thomas E. Dewey, the governor

of New York who had run a respectable but losing race four years earlier

against Franklin Roosevelt, and Governor Earl Warren of California were

anointed the party's standard bearers. The G.O.P.'s platform pledged backing

for a "bipartisan foreign policy" against the Soviet Union while simultaneously

attacking the Democratic administration for its failure to render all-out

aid to Chang Kai-sheck's embattled Nationalist Chinese forces in the civil

war against communist leader Mao Tse-tung. Delegates endorsed statements

supporting increased housing and civil rights legislation. Alluding to

reputed infiltration of the Truman government by communist sympathizers,

the platform promised to vigorously track down and expose such un-American

elements.

As the traditional Labor Day kickoff of formal campaigning

neared, President Truman, trailing Dewey by significant margins, honed

his strategy aware that the Republican-controlled Congress' failure to

pass anything during the two-week special session provided him an opening.

Writing years later, he recalled his determination to ignore Thurmond and

Wallace, stick to the mainstream, and concentrate his fire on Dewey and

the "Do-Nothing 80th Congress." "While I knew that the southern

dissenters and the Wallace-ites would cost some Democratic votes, my opponent

was the Republican Party. The campaign was built on one issue - the interests

of the people, as represented by the Democrats against the special interests,

as represented by the Republicans and the record of the Eightieth Congress.

I staked the race for the presidency on that one issue."

As the traditional Labor Day kickoff of formal campaigning

neared, President Truman, trailing Dewey by significant margins, honed

his strategy aware that the Republican-controlled Congress' failure to

pass anything during the two-week special session provided him an opening.

Writing years later, he recalled his determination to ignore Thurmond and

Wallace, stick to the mainstream, and concentrate his fire on Dewey and

the "Do-Nothing 80th Congress." "While I knew that the southern

dissenters and the Wallace-ites would cost some Democratic votes, my opponent

was the Republican Party. The campaign was built on one issue - the interests

of the people, as represented by the Democrats against the special interests,

as represented by the Republicans and the record of the Eightieth Congress.

I staked the race for the presidency on that one issue."

What followed became political legend and remains

a maxim to this day for both frontrunners and underdogs that elections

are never over until the last vote is counted.

Assured by every public opinion poll that the election

was but a formality and victory was already in the bag, Governor Dewey

tried to sit on his lead. He preached national unity and campaigned in

a less than vigorous manner. His overriding goal was not to alienate voters

who were already displeased with Truman. Accordingly, his defense of the

80th Congress was almost nonexistent and he spoke only in platitudes.

In stark contrast, President Truman hit the road,

waging a whistle stop campaign to appeal to the people and solidify the

votes of wavering elements of the Roosevelt Coalition. Travelling by train

throughout the country, he spoke wherever people would gather to listen.

As he railed against the Republican Congress, derided his opponent as "the

little man on the top of a wedding cake," and reminded voters of what the

Democratic Party had done for them since the dark days of the Great Depression,

he began making headway. The crowds kept getting larger and larger. To

cries of "Give 'Em Hell Harry," he fought for his political life. All in

all he traveled more than 31,000 miles and gave well over three hundred

speeches in a period of thirty-five days. At each stop, he lashed out -

"When I called them (Congress) back into session what did they do? Nothing.

Nothing. That Congress never did anything the whole time it was in session."

Republicans, he alleged, were "predatory animals who don't care if you

people are thrown into a depression." He appealed to minority racial and

religious groups in the urban northeast but ignored the civil rights issue

in his trips into Dixie. Special attention was paid to organized labor

throughout the country. Speaking on Labor Day to automobile workers at

Cadillac Square in Detroit, Truman thundered:

As you know, I speak plainly sometimes. In

fact, I speak bluntly sometimes. I am going to speak plainly and bluntly today.

These are critical times for labor and for all who work. There is great

danger ahead. Right now, the whole future of labor is wrapped up in one

single proposition. If, in this next election, you get a Congress and an

administration friendly to labor, you have much to hope for. If you get

an administration, and a Congress unfriendly to labor, you have much to

fear, and you had better look out…

If the Congressional elements that made the Taft-Hartley

Law are allowed to remain in power, and if these elements are further encouraged

by the election of a Republican President, you men of labor can expect

to be hit by a steady barrage of body blows. And, if you stay at home,

as you did in 1946, and keep these reactionaries in power, you will deserve

every blow you get….

Each constituency of the Roosevelt Coalition heard how

important it was to return Democrats to office - local, state, and national;

executive, legislative, and judicial. While the crowds continued to grow,

the pollsters continued to predict a sweeping Dewey victory. Even Truman's

advisors and family held out little hope. Speaking to insider Clark Clifford

just days before the election, the president's wife expressed her concern.

"What shall we do for poor Harry, he actually thinks he's going to win."

Indeed he did. After wrapping up the campaign with a nationwide radio address,

Truman took a bath, went upstairs to his room before seven o'clock, ate

a ham sandwich, drank a glass of milk, and went to sleep. Waking early

the next morning, he learned he was over 2,000,000 votes ahead of Dewey

and that Democratic candidates across the country were leading their opponents.

By eleven o'clock that morning he was handed Governor Dewey's telegram

congratulating him on his victory.

Truman had, in fact, defeated Dewey by nearly three

million popular votes - each one hard won on the campaign trail. As the

president had suspected, most of the dissidents within his party had returned

to the fold on Election Day. While the major candidates split 46 million

votes between them, Thurmond and Wallace garnered slightly over a million

apiece. Thurmond had carried only those four states where he had been listed

on the ballot as the Democratic nominee - South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi,

and Louisiana. Wallace carried not a single state but may have cost the

president New York. Victory in the Electoral College was assured; Truman

received 303, Dewey 189, and Thurmond 39.

Truman had, in fact, defeated Dewey by nearly three

million popular votes - each one hard won on the campaign trail. As the

president had suspected, most of the dissidents within his party had returned

to the fold on Election Day. While the major candidates split 46 million

votes between them, Thurmond and Wallace garnered slightly over a million

apiece. Thurmond had carried only those four states where he had been listed

on the ballot as the Democratic nominee - South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi,

and Louisiana. Wallace carried not a single state but may have cost the

president New York. Victory in the Electoral College was assured; Truman

received 303, Dewey 189, and Thurmond 39.

Nor was victory Truman's alone. In fact, one could

argue that in many areas of the country he benefited from a "reverse coattails"

phenomenon. The coattail effect refers to a popular presidential candidate's

ability to sweep other candidates of his party into office. In this case,

the opposite appears to have occurred. While the president carried most

traditionally Democratic states, his vote totals and margins of victory

were less than other party candidates. Truman, in a sense, clutched the

coattails of congressional, gubernatorial, and state candidates of his

own party and benefited from their strength at the ballot box. Democrats

had reason to rejoice after all the votes had been counted. Party candidates

had regained control of both the House of Representatives and the Senate

in the nation's capitol, picking up seventy-five seats in the lower chamber

and a total of nine in the upper body. Gubernatorial candidates were successful

as well, winning twenty of the thirty-two contested races.

Conclusion and Meaning

All the experts had gotten it wrong - dead wrong.

In a state of shock and embarrassment, pollsters and prognosticators searched

in the aftermath for answers. Within days, the Gallup organization stated

that its fatal mistake had been in halting polling operations ten days

before the election. So confident were they in a Dewey victory, they overlooked

the possibility that millions of "undecided" voters would swing overwhelmingly

to the combative incumbent at the last possible moment. George Gallup vowed

that the mistake would never happen again.

There was in fact a monumental and last minute shift

to Truman by voters who had identified themselves as "undecided" until

the very last. Such a shift, however, should not have been surprising given

a number of factors. The president had campaigned with all the vigor he

could muster while Governor Dewey forgot to make his and the Republican

Party's case to the American voter. Truman pursued those voters, asked

for their support, and gave Democrats a reason to vote while Dewey and

many Republicans waited confidently for inauguration day. There was both

the "reverse coattails" phenomenon and Truman's decision to keep to the

political mainstream, trusting that realists to both his right and left

would abandon the folly of minor party candidates when casting their ballots.

Most importantly, enough of the Roosevelt Coalition remained loyal when

it counted. Truman suffered a setback in deepest Dixie, but carried the

other core elements of the coalition, racking up the votes of organized

labor, religious and ethnic minorities, the majority of moderates and liberals,

academia, etc.

The election of 1948 marked a turning point in American

politics. While victorious at the ballot box, the next four years would

not be kind to Harry Truman. His days would be spent fighting unsuccessfully

against a coalition of conservative Democrats and Republicans to make his

Fair Deal legislative reality. Scandals drove down his approval rating

to all-time lows. Republican conservatives seized upon the "loss of China"

to the socialist world, the attack upon South Korea by communists which

resulted in a protract and unpopular war, and the issue of internal security

gone awry to pummel Democrats over the next four years. Nonetheless, Truman

would triumph in the end. His domestic and foreign policy initiatives dominated

the American agenda for the next half-century. Issues such as national

health care, social security, and civil rights remain as pivotal to the

nation's future at the beginning of the twenty-first century as in 1948.

While vilified by critics at the time, historians today recognize that

the irascible Missourian met monumental challenges with fortitude and success

under the most trying of circumstances. The most recent comparisons of

presidential performance rate Truman in the "near great" category.

The Democratic Party's solid southern base would,

however, never be the same. While tensions had existed for decades between

the various wings of the party, it had always recovered. In the largest

sense, there was no recovery from 1948. While only four states had abandoned

the party of Jackson, Cleveland, Wilson, and Roosevelt that year, defection

became less and less unthinkable with each election cycle. When President

Lyndon Johnson, a Democrat from Texas, engineered congressional passage

of sweeping civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s the transition could

no longer be forestalled. Southerners now perceived the Republican Party,

so long discredited in Dixie because of the Civil War and Reconstruction

eras, as the party of conservatives and whites. Feeling abandoned by their

party, voters began flocking in ever-larger numbers to the Republican standard.

Regional realignment became an accomplished fact. The "solid south" still

exists but, unlike 1948, it today belongs to the Grand Old Party.

(c) L. Patrick Hughes, 2000

_______________________________________________________________________

Appendix # 1

It seems to me that the Democratic Party needs to

make definite pledges of the kind suggested in the minority report, to

maintain the trust and confidence placed in it by the people of all races

and all sections of this country. Sure, we are here as Democrats, but,

my good friends, we are here as Americans; we are here as the believers

in the principles and the ideology of democracy, and I firmly believe that

as men concerned with our country's future, we must specify in our platform

the guarantees which we have mentioned in the minority plank.

Yes, this is far more than a party matter. Every

citizen in this country has a stake in the emergence of the United States

as a leader in the free world. That world is being challenged by the world

of slavery. For us to play our part effectively, we must be in a morally

sound position.

We cannot use a double standard. There is no room

for double standards in American politics. For measuring our own and other

people's politics, our demands for democratic practices in other lands

will be no more effective than the guarantees of those practiced in our

own country.

We are God-fearing men and women. We place our faith

in the brotherhood of man under the fatherhood of God.

Friends, delegates, I do not believe that there can

be any compromise of the guarantees of civil rights which we have mentioned

in the minority report. In spite of my desire for unanimous agreement on

the entire platform, in spite of my desire to see everybody here in unanimous

agreement, there are some matters which I think must be stated clearly

and without qualification. There can be no hedging - no watering down.

The newspaper headlines are wrong.

There will be no hedging, and there will be no watering

down, if you please, of the instruments and the principles of the civil

rights program.

My friends, to those who say that we are rushing

this issue of civil rights, I say we are 172 years too late!

To those who say that this civil rights program is

an infringement on states' rights, I say this, that the time has arrived

in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadows of states'

rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.

People, human beings, this is the issue of the Twentieth

Century, people of all kinds, and these people are looking to America for

leadership and they are looking to America for precepts and examples.

My good friends and my fellow Democrats, I ask you

for a calm consideration of our historic opportunity. Let us forget the

evil patience and the blindness of the past. In these times of world economic,

political and spiritual -above all, spiritual - crisis we cannot, and we

must not, turn from the paths so plainly before us.

That path has already led us through many valleys

of the shadow of death, and now is the time to recall those who were left

on that path of American freedom.

To all of us here, for the millions who has sent

us, for the whole two billion members of the human family - our land is

now, more than ever, the last best hope on earth. I know that we can, I

know that we shall begin here the fuller and richer example of that - that

promise of a land where all men are free and equal, and each man uses his

freedom and equality wisely and well.

My good friends, I ask my Party, and I ask the Democratic

Party to march down the high road of progressive democracy. I ask this

convention to say in unmistakable terms that we proudly hail and we courageously

support our President and leader, Harry Truman, in his great fight for

civil rights in America.

Appendix #2 Gallup

Poll Test Heats

The embattled president had additional reason to

look past the doom and gloom of the current situation. A seasoned political

veteran, he was aware that many of his critics of spring and summer would

probably return to the fold on Election Day, especially if he gave them

reason to do so. Throughout the republic's history, early rhetorical support

for third- and fourth-party insurgents inexorably evaporates in the harsh

light of November reality. Third parties never win, or so

the overwhelming majority of Americans believe. Therefore, a ballot cast

for a minor party candidate may give vent to the spleen but forfeits any

impact on the outcome of the real contest between major party nominees.

Even when less than satisfied with the major contenders, most citizens

swallow hard and vote for the one considered less objectionable. Such an

oft-repeated phenomenon was likely to reoccur yet again in 1948. The key

for Truman was in persuading the majority of the temporarily dissatisfied

that he was the least objectionable of the viable alternatives. Some events,

however, were beyond his control as delegates to the Democratic nominating

convention began assembling in Philadelphia.

The embattled president had additional reason to

look past the doom and gloom of the current situation. A seasoned political

veteran, he was aware that many of his critics of spring and summer would

probably return to the fold on Election Day, especially if he gave them

reason to do so. Throughout the republic's history, early rhetorical support

for third- and fourth-party insurgents inexorably evaporates in the harsh

light of November reality. Third parties never win, or so

the overwhelming majority of Americans believe. Therefore, a ballot cast

for a minor party candidate may give vent to the spleen but forfeits any

impact on the outcome of the real contest between major party nominees.

Even when less than satisfied with the major contenders, most citizens

swallow hard and vote for the one considered less objectionable. Such an

oft-repeated phenomenon was likely to reoccur yet again in 1948. The key

for Truman was in persuading the majority of the temporarily dissatisfied

that he was the least objectionable of the viable alternatives. Some events,

however, were beyond his control as delegates to the Democratic nominating

convention began assembling in Philadelphia.